Experts in autocracies have pointed out that it is, unfortunately, easy to slip into normalizing the tyrant, hence it is important to hang on to outrage. These incidents which seem to call for the efforts of the Greek Furies (Erinyes) to come and deal with them will, I hope, help with that. As a reminder, though no one really knows how many there were supposed to be, the three names we have are Alecto, Megaera, and Tisiphone. These roughly translate as “unceasing,” “grudging,” and “vengeful destruction.”

As I’ve been saying, I have a number of articles saved regarding how white supremacy thinks, when it increases, how it expresses itself, and so on – and especially, what to do about it. I hope to get to all of them eventually. This is one of them. It’s about the conditions which tend to give rise to populism.

Since “populism” just means “people-ism,” and democracy is supposed to be government of, for, and by the people, you may wonder how this could be bad. But “populism” in politics has its own definition. And it turns out to be quite unfavorable to actual people.

================================================================

Populism erupts when people feel disconnected and disrespected

Caroline Brehman/CQ-Roll Call, Inc via Getty Images

Noam Gidron, Hebrew University of Jerusalem and Peter A. Hall, Harvard University

American society is riven down the middle. In the 2020 presidential election, 81 million people turned out to vote for Joe Biden, while another 74 million voted for Donald Trump. Many people came to the polls to vote against the other candidate rather than enthusiastically to support the one who secured their vote.

While this intense polarization is distinctly American, born of a strong two-party system, the antagonistic emotions behind it are not.

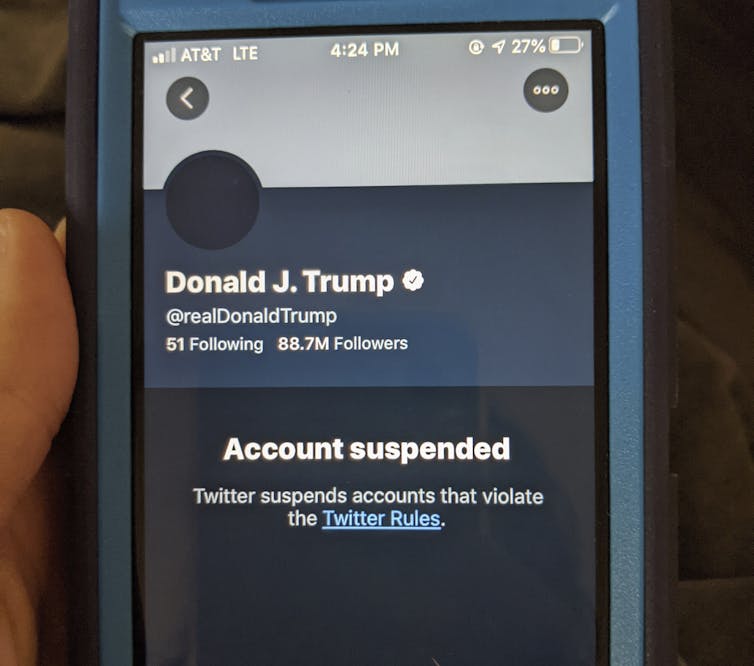

Much of Trump’s appeal rested on a classically populist message – a form of politics evident around the world that rails against mainstream elites on behalf of the ordinary people.

The resonance of those appeals means that America’s social fabric is fraying at its edges. Sociologists refer to this as a problem of social integration. Scholars argue that societies are well integrated only when most of their members are closely connected to other people, believe that they are respected by others and share a common set of social norms and ideals.

Although people voted for Donald Trump for many reasons, there is growing evidence that much of his appeal is rooted in problems of social integration. Trump seems to have secured strong support from Americans who feel they have been pushed to the margins of mainstream society and who may have lost faith in mainstream politicians.

This perspective has implications for understanding why support for populist politicians has recently been rising around the world. This development is the subject of widespread debate between those who say populism stems from economic hardship and others who emphasize cultural conflict as the source of populism.

Understanding populism’s roots is essential for addressing its rise and threat to democracy. We believe seeing populism as the product not of economic or cultural problems, but as a result of people feeling disconnected, disrespected and denied membership in the mainstream of society, will lead to more useful answers about how to stem populism’s rise and strengthen democracy.

Probal Rashid/LightRocket via Getty Images

Not only in America

One Democratic pollster found that support for Trump in 2016 was high among people with low trust in others. In 2020, polling found that “socially disconnected voters were far more likely to view Trump positively and support his reelection than those with more robust personal networks.”

Our analysis of survey data from 25 European countries suggests that this is not a purely American phenomenon.

These feelings of social marginalization and a corresponding disillusionment with democracy provide populist politicians of all hues and from different countries with an opportunity to claim that the mainstream elites have betrayed the interests of their hard-working citizens.

Across all of these countries, it turns out that people who engage in fewer social activities with others, mistrust those around them and feel that their contributions to society go largely unrecognized are more likely to have less trust in politicians and lower satisfaction with democracy.

Marginalization affects voting

Feelings of social marginalization – reflected in low levels of social trust, limited social engagement and the sense that one lacks social respect – are also linked to whether and how people vote.

People who are socially disconnected are less likely to turn out to vote. But, if they do decide to vote, they are significantly more likely to support populist candidates or radical parties – on either side of the political spectrum – than people who are well integrated into society.

This relationship remains strong even after other factors that might also explain voting for populist politicians, such as gender or education, are taken into account.

There is a striking correspondence between these results and the stories told by people who find populist politicians attractive. From Trump voters in the American South to radical right supporters in France, a series of ethnographers have heard stories about failures of social integration.

Populist messages, like “take back control” or “make America great again,” find a receptive audience among people who feel pushed to the sidelines of their national community and deprived of the respect accorded full members of it.

Intersection of economics and culture

Once populism is seen as a problem of social integration, it becomes apparent that it has both economic and cultural roots that are deeply intertwined.

Economic dislocation that deprives people of decent jobs pushes them to the margins of society. But so does cultural alienation, born when people, especially outside large cities, feel that mainstream elites no longer share their values and, even worse, no longer respect the values by which they have lived their lives.

These economic and cultural developments have for long shaped Western politics. Therefore, electoral losses of populist standard bearers such as Trump do not necessarily herald the demise of populism.

The fortunes of any one populist politician may ebb and flow, but draining the reservoir of social marginalization on which populists depend requires a concerted effort for reform aimed at fostering social integration.

[Understand key political developments, each week. Subscribe to The Conversation’s election newsletter.]![]()

Noam Gidron, Assistant Professor of Political Science,, Hebrew University of Jerusalem and Peter A. Hall, Krupp Foundation Professor of European Studies, Harvard University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

================================================================

Alecto, Megaera, and Tisiphone, the authors of this article recommend “fostering social integration” as a major project to safeguard our nation against future insurrections motivated by populism, but they don’t really have much to say on how to go about accomplishing that. I submit that public education is a major factor – and the fact that our system of public education has been so dramatically undermined over the last 40 years is a major contributor to the current dangerous populism. One aspect of becoming and being integrated into society is understanding how to know what people or kinds of people can be trusted, and which cannot. A good education can provide and strengthen that kind of discernment.

I also grant that it is extremely challenging to show respect toward people whose opinions and behavior have amply demonstrated they deserve none. But – they are still human being, and they do deserve to be respected as such, even with all their attempts to deny the same to others. It will require a lot of work – and a lot of self control.

The Furies and I will be back.