Experts in autocracies have pointed out that it is, unfortunately, easy to slip into normalizing the tyrant, hence it is important to hang on to outrage. These incidents which seem to call for the efforts of the Greek Furies (Erinyes) to come and deal with them will, I hope, help with that. As a reminder, though no one really knows how many there were supposed to be, the three names we have are Alecto, Megaera, and Tisiphone. These roughly translate as “unceasing,” “grudging,” and “vengeful destruction.”

The number – and the names – we have lost to pancreatic cancer in the last couple od decades is staggering. Mercifully, I can’t offhand remember many of the names besides Alex Trebek, but I also cannot get over the “Oh my god, no not again” feeling when I see the words next to someone’s name. With this article I have a better idea of why, and maybe even a little hope.

==============================================================

Stopping the cancer cells that thrive on chemotherapy – research into how pancreatic tumors adapt to stress could lead to a new treatment approach

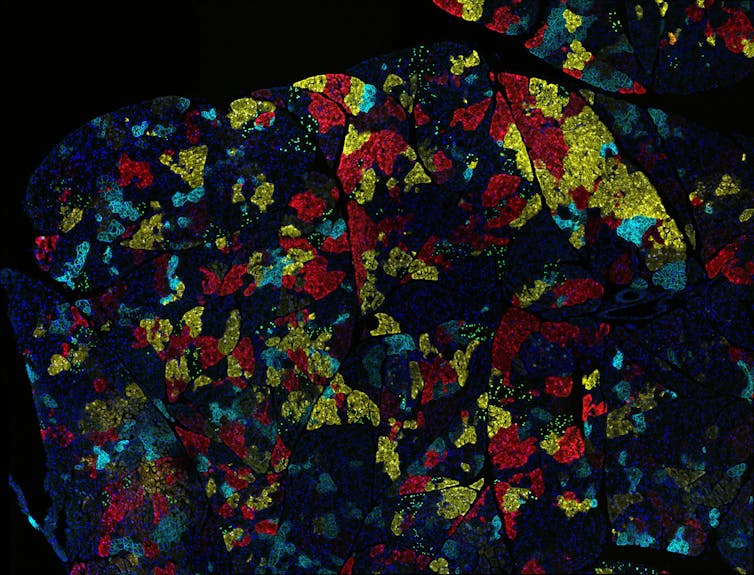

Steve Seung-Young Lee, Univ. of Chicago Comprehensive Cancer Center, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health via Flickr, CC BY-NC

Chengsheng Wu, University of California, San Diego; David Cheresh, University of California, San Diego, and Sara Weis, University of California, San Diego

As with weeds in a garden, it is a challenge to fully get rid of cancer cells in the body once they arise. They have a relentless need to continuously expand, even when they are significantly cut back by therapy or surgery. Even a few cancer cells can give rise to new colonies that will eventually outgrow their borders and deplete their local resources. They also tend to wander into places where they are not welcome, creating metastatic colonies at distant sites that can be even more difficult to detect and eliminate.

One explanation for why cancer cells can withstand such inhospitable environments and growing conditions is an old adage: What doesn’t kill them makes them stronger.

At the very earliest stage of tumor formation, even before cancer can be diagnosed, individual cancer cells typically find themselves in an environment lacking nutrients, oxygen or adhesive proteins that help them attach to an area of the body to grow. While most cancer cells will quickly die when faced with such inhospitable conditions, a small percentage can adapt and gain the ability to initiate a tumor colony that will eventually become malignant disease.

We are researchers studying how these microenvironmental stresses affect tumor initiation and progression. In our new study, we found that the harsh microenvironments of the body can push certain cancer cells to overcome the stress of being isolated and make them more adept at initiating and forming new tumor colonies. Moreover, these cancer cells may adapt even better in the inhospitable and stressful conditions they encounter while trying to establish metastases in other areas of the body or after they are challenged by treatment with chemotherapy or surgery.

Cancer cells overcoming isolation stress

We focused on pancreatic cancer,

one of the most lethal cancers and one that is notoriously resistant to chemotherapy and often not curable with surgery. Almost 90% of pancreatic patients will succumb to cancer recurrence or metastasis within five years after diagnosis.

We wanted to study how tumor formation is affected by what we call “isolation stress,” when cells are deprived of nutrients or oxygen supply because of poor blood vessel formation or because they cannot benefit from making contact with nearby cancer cells. To study how cancer cells respond to these situations, we recreated different forms of isolation stress in cell cultures, in mice and in patient samples by depriving them of oxygen and nutrients or by exposing them to chemotherapeutic drugs. We then measured which genes were turned on or off in pancreatic cancer cells.

We found that pancreatic cancer cells challenged with conditions that mimic isolation stress gain a new receptor on their surface that unstressed cancer cells don’t typically have: lysophosphatidic acid receptor 4, or LPAR4, a protein involved in tumor progression.

When we forced the cancer cells to produce LPAR4 on their surfaces, we found that they were able to form new tumor colonies two to eight times faster than average cancer cells under isolation stress conditions. Also, preventing cancer cells from gaining LPAR4 when they were stressed reduced their ability to form tumor colonies by 80% to 95%. These findings suggest that the ability of cancer cells to gain LPAR4 when they are exposed to stress is both necessary and sufficient to promote tumor initiation.

Ravikanth Maddipati, Abramson Cancer Center at the Univ. of Pennsylvania, National Cancer Institute, National Institutes of Health via Flickr, CC BY-NC

How does LPAR4 help build tumors?

We also found that LPAR4 helps cancer cells achieve tumor initiation by giving them the ability to produce a web of macromolecules, or an extracellular matrix network, that provides them an adhesive foothold within an otherwise inhospitable environment. By producing a halo of their own matrix, cancer cells with LPAR4 can start building their own tumor-supporting niche that provides a refuge from isolation stresses.

We determined that a key component of this extracellular matrix is fibronectin. When this protein binds to receptors called integrins on the surface of cells, it triggers a cascade of events that results in the expression of new genes promoting tumor initiation, stress tolerance and cancer progression. Eventually, other cancer cells are recruited into the fibronectin-rich matrix network, and a new satellite tumor colony starts to form.

Considering that tumor cells with LPAR4 can create their own tumor-supporting matrix on the fly, this suggests that LPAR4 may allow individual tumor cells to overcome isolation stress conditions and survive in the bloodstream, the lymphatic system involved in immune responses or distant organs as metastases.

Importantly, we found that isolation stress is not the only way to trigger LPAR4. Exposing pancreatic cancer cells to chemotherapy drugs, which are designed to impose stress upon cancer cells, also triggers an increase of LPAR4 on cancer cells. This finding might explain how such tumor cells could develop drug resistance.

Keeping cancer cells stressed

Understanding how to cut off the cascade of events that allows cancer cells to become stress-tolerant is important, because it provides a new area to explore for future treatments.

Our team is currently considering potential strategies to prevent cancer cells from utilizing the fibronectin matrix to gain stress tolerance, including drugs that can target the receptors that bind to fibronectin on the surface of tumor cells. One of these drugs, being developed by a company one of us co-founded, is poised to enter clinical trials soon. Other strategies include preventing cancer cells from gaining LPAR4 when they sense stress, or interfering with the signals that promote the generation of the fibronectin matrix.

For patients diagnosed with pancreatic cancer, there is a pressing need to discover how to improve the effectiveness of surgery or chemotherapy. Like combating weeds in your garden, this may require attacking the problem from multiple directions at once.![]()

Chengsheng Wu, Postdoctoral Scholar in Pathology, University of California, San Diego; David Cheresh, Professor of Pathology, University of California, San Diego, and Sara Weis, Senior Scientist in Pathology, University of California, San Diego

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

==============================================================

Alecto, Megaera, and Tisiphone, this is what is meant by “survival of the fittest.” Pancreatic cancer is a survivor because it is so adaptable – it treats chemo the way Mithridates (at least according to legend) treated poison. It is also a dreadful scourge. Unfortunately, the two qualities are not incompatible. If you have any tips to give the scientists working on this, the whole world will deeply appreciate it.

The Furies and I will be back.