Experts in autocracies have pointed out that it is, unfortunately, easy to slip into normalizing the tyrant, hence it is important to hang on to outrage. These incidents which seem to call for the efforts of the Greek Furies (Erinyes) to come and deal with them will, I hope, help with that. As a reminder, though no one really knows how many there were supposed to be, the three names we have are Alecto, Megaera, and Tisiphone. These roughly translate as “unceasing,” “grudging,” and “vengeful destruction.”

I remember “The Bookdocks” from print newspapers and always found it enlightening. Certainly it pulled no punches.I actually never knew that there was a TV series – not really surprising, as I never subscribed to cable or satellite. But based on what I saw in the papers, I’m not surprised that a very interesting course indeed can be developed from it. I can’t even count how many times I have thought and said and written that people do our best learning through storytelling – that it is far more influential than rstional argument, because it touches, not just the brain, but also the heart – and I could go on – But instead I’ll let Professor March do the sharing.

==============================================================

Why I use ‘The Boondocks’ TV cartoon show to teach a course about race

Chelsea Guglielmino via Getty Images

Kris Marsh, University of Maryland

Unusual Courses is an occasional series from The Conversation U.S. highlighting unconventional approaches to teaching.

Title of course:

“Why Are We Still Talking About Race?”

What prompted the idea for the course?

I am a huge fan of the animated TV series “The Boondocks,” which aired from 2005 to 2014. The show chronicles, through biting sociological and political commentary, the adventures of two boys: Huey Freeman, the older brother and self-described revolutionary left-wing radical, and Riley Freeman, Huey’s younger brother, who embraces and represents the gangster lifestyle. The Freeman brothers grapple with having to move from Chicago to the suburbs to live with their grandfather, Robert Freeman, an easily angered and self-proclaimed civil rights icon. A series of events gave me the idea for the course.

The first was during a faculty meeting that felt as if it were going in slow motion because colleagues were going on and on about one item on a full agenda. I had to fight to keep my alter ego, 8-year-old Riley Freeman and his stereotypical “gangsta” lifestyle, from coming out and shouting “shut up” and “let’s move on.”

At that moment, I thought, maybe I should teach a class on “The Boondocks.”

The second event took place a few semesters later. While training police officers on implicit bias, I felt a burning desire to drop some Huey Freeman-type knowledge on the officers. Ten-year-old Huey is highly intelligent and knowledgeable beyond his years.

Finally, in the summer of 2021, while on a golf course collecting data for a research project on navigating racism, sexism and classism as a Black golfer, I met a Black golfer who was not familiar with “The Boondocks,” but whose family calls him Uncle Ruckus. Uncle Ruckus is another character from the show who is notable because of his disdain for Black people and enjoys dissociating himself from other Black Americans. At that moment, it became clear that I should teach a class using “The Boondocks.”

Notably, the creator of “The Boondocks,” Aaron McGruder, is an alum of the University of Maryland, where I teach my course. “The Boondocks” started as a comic strip in the University of Maryland newspaper, The Diamondback, before becoming a syndicated animated show on network television in 2005.

What does the course explore?

We watch episodes weekly. All of the episodes either directly or indirectly deal with various race-related topics. For instance, through an episode titled “The Story of Gangstalicious,” we debate societal views on Black male masculinity. Through an episode called “The Garden Party,” we discuss xenophobia and related implications post-9/11.

Why is this course relevant now?

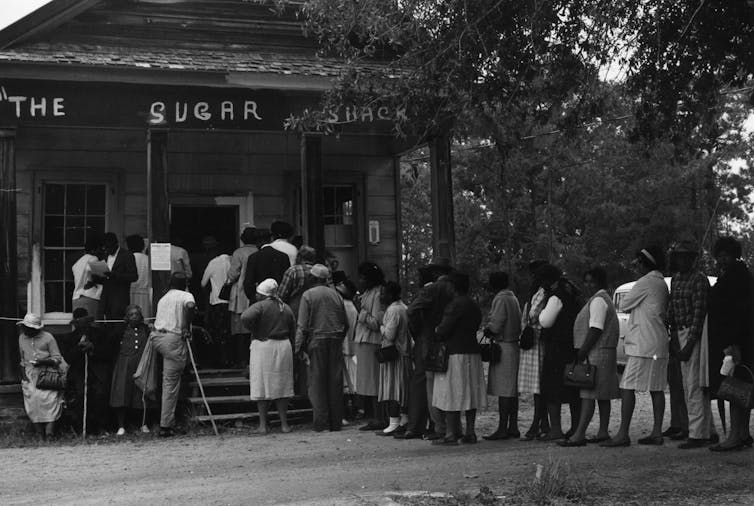

This course explores if and how discussions on race and racism have changed since “The Boondocks” first aired in 2005. The premise and potential relevance of the course lies in the title: “Why Are We Still Talking About Race?” That question refers to 17 years after the first season of “The Boondocks” aired.

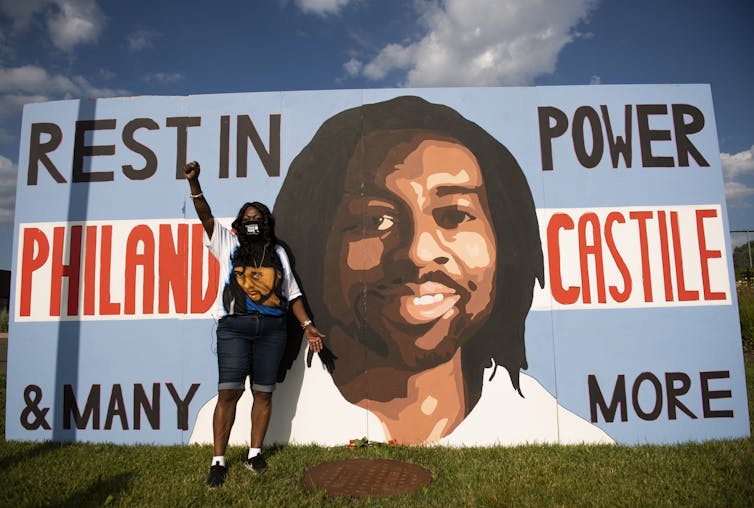

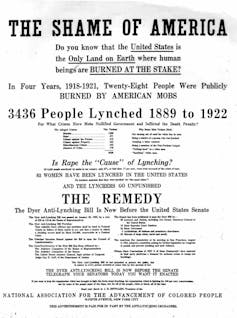

Students are also challenged to look at racism as a phenomenon that is structural and systemic and not just something that happens on an interpersonal level.

Students should be able to connect the episodes to broader and relevant sociological terms and concepts, such as power, privilege, status and how those terms and concepts are related to race and racism.

What’s a critical lesson from the course?

To be clear, the class is not just fandom for “The Boondocks.” Students are actually encouraged to critique “The Boondocks” and how some of the racial commentaries in the episodes are slippery and messy at times. For example, in the “Return of the King” episode, Martin Luther King Jr. was shot but did not die. He was in a coma for more than 30 years.

When King emerges from the coma, he is disappointed as well as upset at how Black people are acting and chastises them. However, the episode seems to admonish Black people and Black culture for their current status without a clear nod to anti-Blackness in social institutions. The lesson for students is to contemplate where they fit into the debate and how their views are shaped and informed by their standpoint and perspective.

What materials does the course feature?

Tuesdays – following the advice of my graduate students – we watch the episodes on our own time. This protects students to make sure no one is offended when their classmates are laughing at aspects of the episode that others might not find funny.

Thursdays we discuss and submit summaries of the episodes we watched on Tuesday. The discussions and summaries should include both a sociological term, concept, theory or idea and a related current event. This requires students to engage with sociological literature and other scholarly readings.

At the start of the course, students sign an agreement that prohibits hate speech, harassment, derogatory language and racial epithets or slurs. The agreement also includes a safe word for students to use if they feel uncomfortable at any point in the classroom.

What will the course prepare students to do?

The course gives students the vocabulary and the ability to discuss race and racism on both the individual and structural levels. The course also prepares students for conversations about race and racism both inside as well as outside of the classroom. For example, we discuss the unacceptable usage of the n-word, and all its derivatives, by non-Black speakers and the links to history and privilege, as dealt with in “The S-Word” episode.![]()

Kris Marsh, Associate Professor of Sociology, University of Maryland

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

==============================================================

Alecto, Megaera, and Tisiphone, yeah, I should have featured this last month – but it was not yet available. And besides, the lines between all the various forms of racism, misogyny, LBGTQIAphobia, and all other forms of othering, are as fine as spider webs and as fragile. Humans are capable of breaking right through them – if only we want to. Help us want to!

The Furies and I will be back.