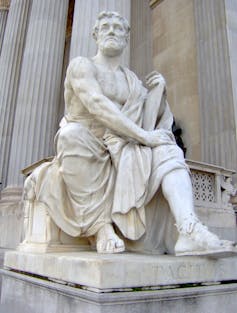

Experts in autocracies have pointed out that it is, unfortunately, easy to slip into normalizing the tyrant, hence it is important to hang on to outrage. These incidents which seem to call for the efforts of the Greek Furies (Erinyes) to come and deal with them will, I hope, help with that. As a reminder, though no one really knows how many there were supposed to be, the three names we have are Alecto, Megaera, and Tisiphone. These roughly translate as “unceasing,” “grudging,” and “vengeful destruction.”

There are two areas which I can’t really cover with the Erinyes, because they are just too big, and because they are not stable but fluid in nature, and even one of those reasons would make either topic unmanageable. Those subjects are war and impeachment. They are also pretty much what is in the news at this point

But it’s never the wrong time for a little education So here is some.

==================================================================

What everyone should know about Reconstruction 150 years after the 15th Amendment’s ratification

National Museum of African American History and Culture

Tiffany Mitchell Patterson, West Virginia University

I’ll never forget a student’s response when I asked during a middle school social studies class what they knew about black history: “Martin Luther King freed the slaves.”

Martin Luther King Jr. was born in 1929, more than six decades after the time of enslavement. To me, this comment underscored how closely Americans associate black history with slavery.

While shocked, I knew this mistaken belief reflected the lack of time, depth and breadth schools devote to black history. Most students get limited information and context about what African Americans have experienced since our ancestors arrived here four centuries ago. Without independent study, most adults aren’t up to speed either.

For instance, what do you know about Reconstruction?

I’m excited about new resources for teaching children, and everyone else, more about the history of slavery through The New York Times’ “1619 Project.” But based on my experience teaching social studies and my current work preparing social studies educators, I also consider understanding what happened during the Reconstruction essential for exploring black power, resilience and excellence.

During that complex period after the Civil War, African Americans gained political power yet faced the backlash of white supremacy and racial violence. I share the concerns many writers, historians and other scholars are raising about the shortcomings of what schoolchildren traditionally learn

about Reconstruction in school. Here are some suggestions for educators and others interested in learning more about that time period.

Reconstruction amendments

As most students do learn, the U.S. gained three constitutional amendments that extended civil and political rights to newly freed African Americans following the Civil War.

The 13th, ratified in 1865, banned slavery and involuntary servitude except for the punishment of a crime.

The 14th, ratified three years later, granted citizenship and equal protection under the law to all people born in the United States, as well as naturalized citizens – including all previously enslaved individuals.

Then, the 15th Amendment asserted that neither the federal government nor state governments could deny voting rights to any male citizen.

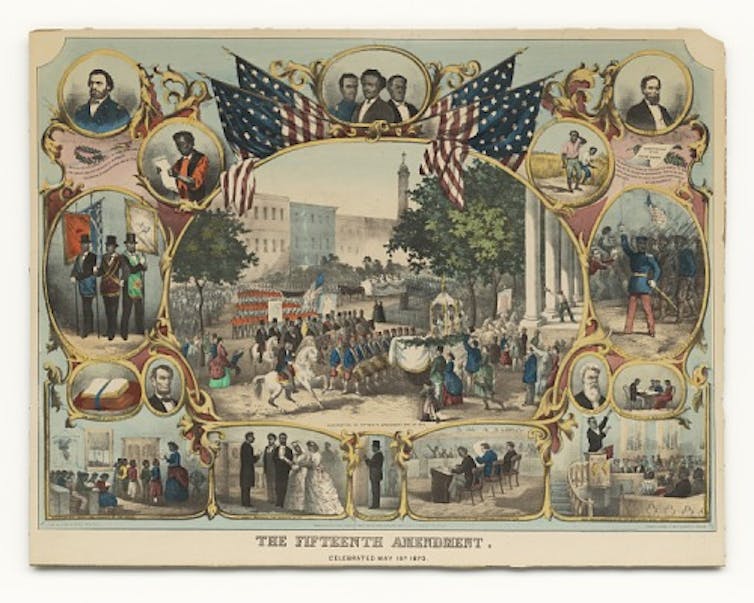

The year 2020 marks the 150th anniversary of the ratification of the 15th Amendment on Feb. 3, 1870. The anniversary is a good opportunity to learn about how the amendment was supposed to guarantee that the right to vote could not be denied based on “race, color, or previous condition of servitude.”

Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture

African American politicians

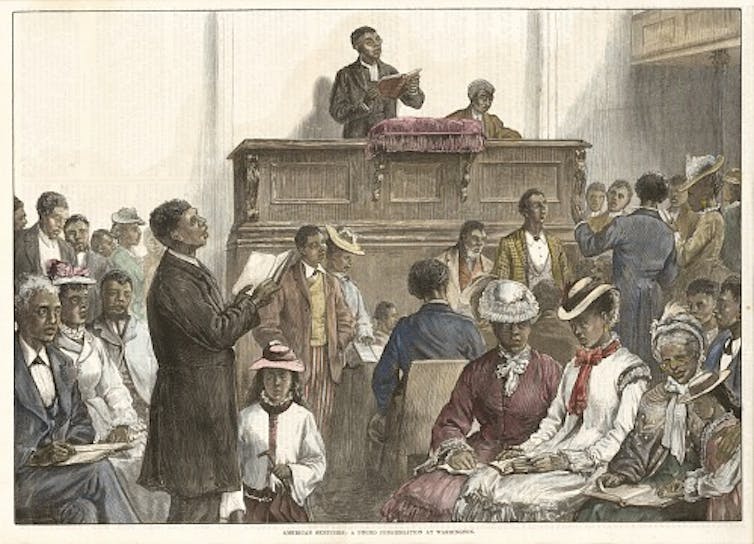

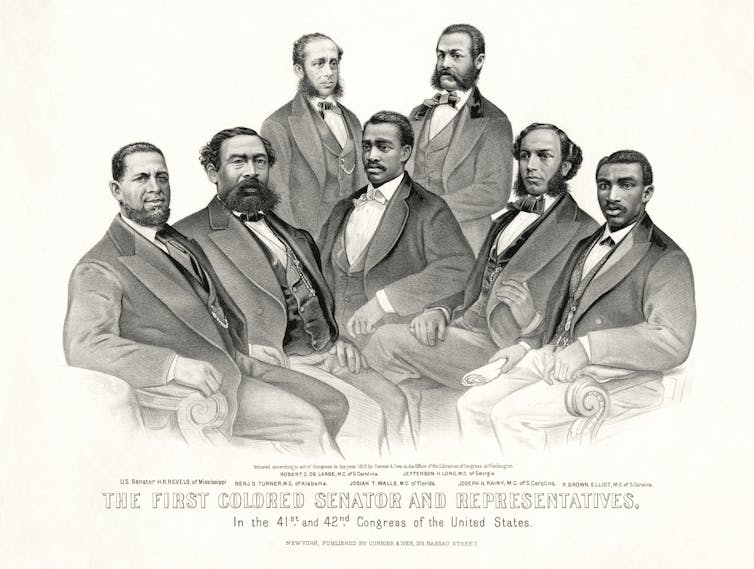

What few history and social studies classes explore is how these changes to the Constitution made it possible for African American men to use their newfound political power to gain representation.

Hiram Rhodes Revels, the first African American senator, represented Mississippi in 1870 after the state’s Senate elected him. He was among the 16 black men from seven southern states who served in Congress during Reconstruction.

Revels and his colleagues were only part of the story. All told, about 2,000 African Americans held public office at some level of government during Reconstruction.

White supremacist groups like the Ku Klux Klan also formed following the Civil War. These terrorist groups engaged in violence and other racist tactics to intimidate African Americans, people of color, black voters and legislators. They thus made the accomplishments of African American politicians even more impressive as they served as public officials under the constant threat of racial violence.

Currier and Ives via the Library of Congress

Black activist women

African American women technically gained the right to vote in 1920, when the 19th Amendment passed. However, their constitutional right was limited in many states due to discriminatory laws.

National Archives Docs Teach collection

Many black women were activists and women’s suffrage movement leaders. Through public speaking, prolific writing and developing organizations dedicated to racial and and gender equality, they fought for equal rights and dignity for all.

Among the black women who were activists during Reconstruction were

the five Rollins sisters of South Carolina, who fought for female voting rights; Maria Stewart, an outspoken abolitionist before the Civil War and suffragist once it ended; and Mary Ann Shadd Cary, the first black woman in North America to edit and publish a newspaper, one of the first black female lawyers in the country and an advocate for granting women the right to vote.

Other women of color who played key roles in the suffrage movement included Ida B. Wells, the journalist and civil rights advocate who raised awareness of lynching, and Mary Church Terrell, founder of the National Association of Colored Women.

Higher education

Before the Civil War, many states made teaching enslaved individuals to read a crime. Education quickly became a top priority for black Americans once slavery ended.

While northern, largely white philanthropists and missionary groups and the U.S. Bureau of Refugees, Freedmen, and Abandoned Lands, better known as the Freedmen’s Bureau, did help create new educational opportunities, the African American public schools established after the Civil War ended were largely built and staffed by the black community.

Many new institutions of higher education, now called Historically Black Colleges and Universities or HBCUs, began to operate during Reconstruction.

These schools trained black people to become teachers and ministers, doctors and nurses. They also prepared African Americans for careers in industrial and agricultural fields.

Public and private HBCUs founded during Reconstruction and still operating today include Howard University in Washington, D.C., Hampton University in Virginia, Alabama State University, Morehouse College in Georgia and Morgan State University in Maryland. These colleges and universities train a disproportionate share of black doctors and other professionals even today.

Official White House Photo by Pete Souza

Historical experiences

Storytelling, multimedia experiences and trips to historic sites and creative museums help get people of any age interested in learning about history.

Depending on where you live, you may want to embark on a family outing or school field trip.

The National Constitution Center in Philadelphia has a new permanent exhibit on the Civil War and Reconstruction.

The National Museum of African American History and Culture, which opened in Washington, D.C. in 2017, contains artifacts from the Reconstruction era. It’s also making the records of the Freedmen’s Bureau, including the names of formerly enslaved individuals following the Civil War, available online.

Another option is the Reconstruction Era National Historic Park in Beaufort County, South Carolina.

I also recommend watching the PBS documentaries about Reconstruction by the scholar and filmmaker Henry Louis Gates Jr. and reading the young adult book Gates co-authored with children’s nonfiction writer Tonya Bolden about the era. Gates has also compiled a Reconstruction reading list for adults.

In addition, the organization Teaching for Change curates a booklist on Reconstruction for middle and high school students. And the Zinn Education Project Teach Reconstruction Campaign offers a variety of resources including readings, primary sources and even lesson plans.

An incomplete transition

As the renowned black scholar W.E.B. DuBois observed, racist laws and violent tactics in many states actively limited black freedom.

“The slave went free; stood for a brief moment in the sun; then moved back again toward slavery,” he explained.

This was by no means voluntary. Intimidated and threatened by black enfranchisement and excellence in the era of Reconstruction, white supremacists attempted to enforce subordination through violence, such as lynching; and in systemic ways through Jim Crow laws. African Americans continued to assert their civil and constitutional rights as activists, politicians, business owners, teachers and farmers in the midst of white supremacist backlash.

With the latest voter suppression efforts restricting access to the ballot box for voters of color and the resurgence of racist violence and vitriol today, DuBois’ words sound eerily familiar. At the same time it’s reassuring to recall how quickly formerly enslaved African Americans made their way to schoolhouses and public offices.

[ Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter. ]![]()

Tiffany Mitchell Patterson, Assistant Professor of Secondary Social Studies, West Virginia University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

==================================================================

Alecto, Megaera, and Tisiphone, This overview just really scratches the surface. I have seen Dr. Gates’s documentary, and it goes deeper (and I’m delighted to know that it’s currently available to stream. Not everything always is. I may have to bite the bullet and purchase it.) But at least this overview will give anyone who wasn’t aware an idea of just how much we weren’t aware of. Especially since we appear currently to be paying a huge price for not knowing our full and accurate history. Perhaps you can lead us to more resources for deeper learning.

The Furies and I will be back.