Experts in autocracies have pointed out that it is, unfortunately, easy to slip into normalizing the tyrant, hence it is important to hang on to outrage. These incidents which seem to call for the efforts of the Greek Furies (Erinyes) to come and deal with them will, I hope, help with that. As a reminder, though no one really knows how many there were supposed to be, the three names we have are Alecto, Megaera, and Tisiphone. These roughly translate as “unceasing,” “grudging,” and “vengeful destruction.”

The Furies picked out this article themselves. They wanted us to get a better handle on how events of today are reflected in events of days when they were very young. They hope it will help.

==================================================================

The ancient Greeks had alternative facts too – they were just more chill about it

Jacopo Tintoretto’s The Muses/Wikpedia

Joel Christensen, Brandeis University

In an age of deepfakes and alternative facts, it can be tricky getting at the truth. But persuading others – or even yourself – what is true is not a challenge unique to the modern era. Even the ancient Greeks had to confront different realities.

Take the story of Oedipus. It is a narrative that most people think they know – Oedipus blinded himself after finding out he killed his father and married his mother, right?

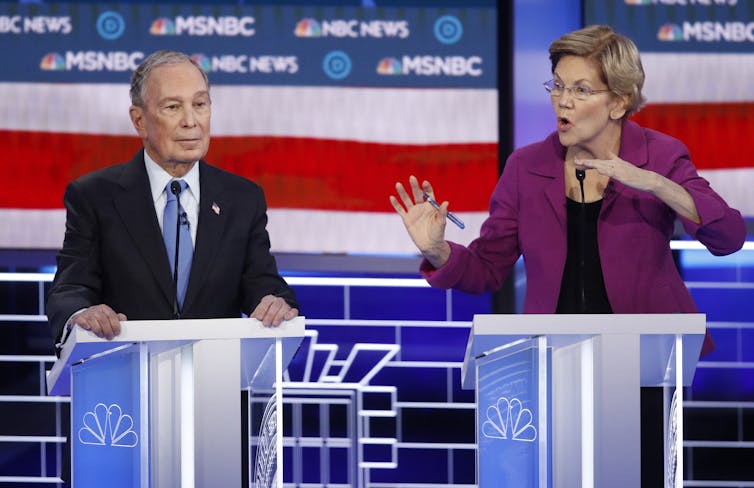

AP Photo

But the ancient Greeks actually left us many different versions of almost every ancient tale. Homer has Oedipus living on, eyes intact after his mother Jocasta’s death. Euripides, another Greek dramatist, has Oedipus continue living with his mother after the truth is revealed.

A challenge I face when teaching Greek mythology is the assumption that my course will establish which version of the story is correct. Students want to know which version is “the right one.”

To help them understand why this isn’t the best approach, I use a passage from Hesiod’s “Theogony,” a story of the origin of the universe and the gods by the poet Hesiod. The narrator claims the Muses, inspirational goddesses of the arts, science and literature, appeared to him and declared “we know how to tell many false things (pseudea) similar to the truth (etumoisin) but we know how to speak the truth (alêthea) when we want to.”

Now, that is quite the disclaimer before going on to describe how Zeus came to rule the universe! But the Greeks had different ways of thinking about narrative and truth than we do today.

The truths are out there

One such approach focuses on the diversity of audiences hearing the story. Under this historical interpretation, the Muses’ caveat can be seen as a way to prepare audiences for stories that differ from those told in their local communities.

A theological interpretation might see a distinction between human beliefs and divine knowledge, reserving the ability to distinguish the truth for the gods alone. This approach anticipates a key tenet of later philosophical distinctions between appearance and reality.

The Muses also set out a metaphysical foundation: The truth exists, but it is hard to comprehend and only the gods can truly know and understand it. This formulation establishes “truth” as a fundamental feature of the universe.

The meanings of the words used are important here. “Pseudea,” used for “lies,” is the root of English compounds denoting something false – think pseudonym or pseudoscience. But notice that Hesiod uses two different words for “truth.” The first, “etumon” is where we get the English etymology from, but this Greek word can mean anything from “authentic” to “original.” The second, “alêthea” literally means “that which is not hidden or forgotten.” It is the root of the mythical river of forgetfulness, Lêthe, whose waters the souls of the dead sample to wash away their memories.

So to the Muses — who were the daughters of Zeus and Mnemosyne, the goddess of memory — “truth” is something authoritative because it is “authentic” in meaning and “revealed” or “unforgettable.”

The Muses’ implication is that truth is derived from ancient origins and is somehow unchanging and, ultimately, unknowable for human beings.

Indeed, this formulation becomes a bedrock of ancient philosophy when authors like Plato insist that truth and reality must be eternal and immutable. Such assumptions about the truth are also central to absolutist approaches to beliefs, whether we are talking about religion, literature or politics.

But what good is knowing about the nature of truth if it is ultimately inaccessible to mortal minds?

From teaching Greek texts I have become increasingly convinced that the Theogony’s narrator quotes the Muses not merely to evade responsibility for telling an unknown story nor to praise the wisdom of the gods. Instead, he is giving us advice for how to interpret myth and storytelling in general: Don’t worry about what it is true or not. Just try to make sense of the story as you encounter it, based on the details it provides.

Myth and memory

The treatment of “truth” in Greek myth can be informative when looking at modern research in cognitive science and memory.

The memory scientist Martin Conway, in studying how people construct stories about the world and themselves, has argued that two basic tendencies, correspondence and coherence, govern our memories.

Correspondence refers to how well our memory fits with verifiable facts, or what actually happened.

Coherence is the human tendency to select details which fit our assumptions about the world and who we are. Conway’s studies show that we tend to select memories about the past and make observations on the present which confirm our own narrative of what actually happened.

We already know that much of what we understand about the world is interpreted and “filled in” by our creative and efficient brains, so it should be of little surprise that we selectively pick memories to represent an absolute truth even as we continually revise it.

As individuals and groups, what we accept as “true” is conditioned by our biases and by what we want the truth to be.

With this in mind, the Muses’ warning not to obsess about whether the details in a myth are true seems appropriate – especially if a narrative making sense is more important than it being “true.”

A scene from Homer’s “Odyssey” strengthens the case for applying these ideas to early Greece. When Odysseus returns to his home island of Ithaca after 20 years, he dons a disguise to test the members of his household. A great deal of suspense arises from his conversations with his wife, Penelope, when he too is described as “someone speaking many lies (pseudea) similar to the truth (etumoisin).” Odysseus presents facts to his wife that have no counterpart in an objective reality, but his selection of details reveals much about Odysseus that is “true” about himself. He offers themes and anecdotes that give an insight into who he is, if we listen closely.

Ancient Greek epics emerged from a culture in which hundreds of different communities with separate traditions and beliefs developed shared languages and beliefs. Not unlike the United States today, this multiplicity created an environment for encountering and comparing differences. What Hesiod’s story tells his audience is that truth is out there, but it is hard work to figure out.

Figuring it out requires us to listen to the stories people tell and think about how they might seem true to them. That means not overreacting when we hear something unfamiliar that goes against what we think we know.

[ Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter.]![]()

Joel Christensen, Associate Professor of Classical Studies, Brandeis University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

==================================================================

Now, I’m sure you are thinking that there is a major difference between truth in myth or religious belief, and truth in actual history. There is indeed. But historians of the times of the Erinyes didn’t see that the way we do. Herodotus, Thucydides, Livy, Tacitus, Pliny, Suetonius, Josephus – All of them included material which cannot be proven true, and material which can actually be proven false. Historians of that time didn’t really seem to care; if it was a good story, they told it.

To give just one example of the provably false, consider the story of Nero “fiddling while Rome burned,” in some accounts watching from the roof of his home. Certainly the great fire burned for several days, and it’s also apparently true that Nero didn’t want to be an Emperor so much as an actor and/or a singer. But fiddled? There was no such thing as a fiddle at the time. There were no bowed stringed instruments at all, and very few plucked ones. There were lyres, which are a sort of two-sided harp. But that’s a minor quibble. What really undercuts the story is that Nero was not in Rome when the fire started – and by the time he did get there, his house – roof and all – no longer existed. (And don’t get me started on the collapsible boat with which he is supposed to have murdered, or tried to murder, his mother Agrippina.) So what you think you know about historical figures may in reality be just as undependable as what you know or don’t know about mythology.

Alecto, Megaera, and Tisiphone, Thank you for sharing with us. Please help us, if you can, to hang onto respect for truth, and to hold on to truth which is knowable and provable, in the face of challenges.

The Furies and I will be back.