Experts in autocracies have pointed out that it is, unfortunately, easy to slip into normalizing the tyrant, hence it is important to hang on to outrage. These incidents which seem to call for the efforts of the Greek Furies (Erinyes) to come and deal with them will, I hope, help with that. As a reminder, though no one really knows how many there were supposed to be, the three names we have are Alecto, Megaera, and Tisiphone. These roughly translate as “unceasing,” “grudging,” and “vengeful destruction.”

Well, Joe has won Pennsylvania, and therefore the presidency. Trump will be gone. Trumpism, unfortunately, will not. Which means our fight is not over. Here is an article with some reasons why, and considerations for what needs to be done.

================================================================

5 reasons not to underestimate far-right extremists

AP Photo/Andrew Selsky

Alexander Hinton, Rutgers University – Newark

Far-right extremists have been in the news, with an alleged plot to kidnap Michigan’s governor and rallies like the one the Proud Boys held in Portland in September.

With a hotly contested election underway in a polarized society, many people are concerned about violence from far-right extremists. But they may not understand the real threat.

The law enforcement community is among those who have failed to understand the true nature and danger of far-right extremists. Over several decades, the FBI and other federal authorities have only intermittently paid attention to far-right extremists. In recent years, they have again acknowledged the extent of the threat. But it’s not clear how long their attention will last.

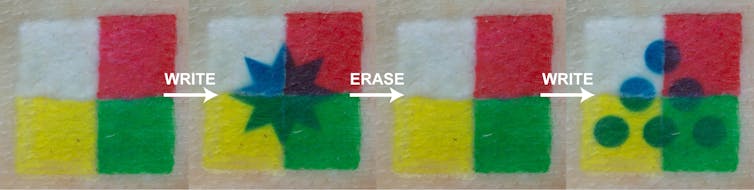

While researching my forthcoming book, “It Can Happen Here: White Power and the Rising Threat of Genocide in the U.S.,” I discovered that there are five key mistakes people make when thinking about far-right extremists. These mistakes obscure the extremists’ true danger.

AP Photo/Mark Humphrey

1. Some have white supremacist views, but others don’t

When asked to condemn white supremacists and extremists at the first presidential debate, President Donald Trump floundered, then said, “Give me a name.” His Democratic challenger Joe Biden offered, “The Proud Boys.”

Not all far-right extremists are militant white supremacists.

White supremacy, the belief in white racial superiority and dominance, is a major theme of many far-right believers. Some, like the Ku Klux Klan and neo-Nazis, are extremely hardcore hate groups.

Others, who at times identify themselves with the term “alt-right,” often mix racism, anti-Semitism and claims of white victimization in a less militant way. In addition, there are what some experts have called the “alt-lite,” like the Proud Boys, who are less violent and disavow overt white supremacy even as they promote white power by glorifying white civilization and demonizing nonwhite people including Muslims and many immigrants.

There is another major category of far-right extremists who focus more on opposing the government than they do on racial differences. This so-called “patriot movement” includes tax protesters and militias, many heavily armed and a portion from military and law enforcement backgrounds. Some, like the Hawaiian-shirt-wearing Boogaloos, seek civil war to overthrow what they regard as a corrupt political order.

AP Photo/Ted S. Warren

2. They live in cities and towns across the nation and even the globe

Far-right extremists are in communities all across America.

The KKK, often thought of as centered in the South, has chapters from coast to coast. The same is true of other far-right extremist groups, as illustrated by the Southern Poverty Law Center’s Hate Map.

Far-right extremism is also global, a point underscored by the 2011 massacre in Norway and the 2019 New Zealand mosque attack, both of which were perpetrated by people claiming to resist “white genocide.” The worldwide spread led the U.N. to recently issue a global alert about the “growing and increasing transnational threat” of right-wing extremism.

AP Photo/Ted S. Warren

3. Many are well-organized, educated and social-media savvy

Far-right extremists include people who write books, wear sport coats and have advanced degrees. For instance, in 1978 a physics professor turned neo-Nazi wrote a book that has been called the “bible of the racist right.” Other leaders of the movement have attended elite universities.

Far-right extremists were early users of the internet and now thrive on social media platforms, which they use to agitate, recruit and organize. The 2017 “Unite the Right” rally in Charlottesville revealed how effectively they could reach large groups and mobilize them into action.

Platforms like Facebook and Twitter have recently attempted to ban many of them. But the alleged Michigan kidnappers’ ability to evade restrictions by simply creating new pages and groups has limited the companies’ success.

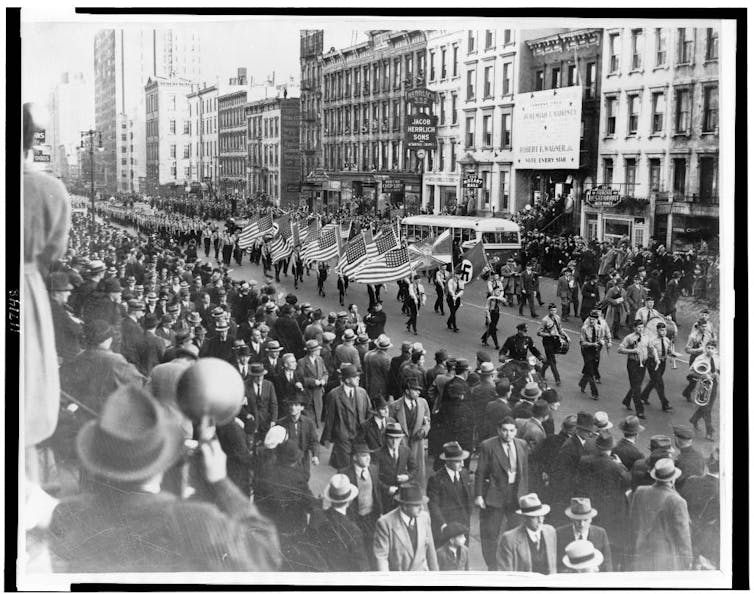

New York World-Telegram and the Sun Newspaper Photograph Collection/Library of Congress

4. They were here long before Trump and will remain here long after

Many people associate far-right extremism with the rise of Trump. It’s true that hate crimes, anti-Semitism and the number of hate groups have risen sharply since his campaign began in 2015. And the QAnon movement – called both a “collective delusion” and a “virtual cult” – has gained widespread attention.

But far-right extremists were here long before Trump.

The history of white power extremism dates back to slave patrols and the post-Civil War rise of the KKK. In the 1920s, the KKK had millions of members. The following decade saw the rise of Nazi sympathizers, including 15,000 uniformed “Silver Shirts” and a 20,000 person pro-Nazi rally at Madison Square Garden in New York City in 1939.

While adapting to the times, far-right extremism has continued into the present. It’s not dependent on Trump, and will remain a threat regardless of his public prominence.

AP Photo/Michael Dwyer

5. They pose a widespread and dire threat, with some seeking civil war

Far-right extremists often appear to strike in spectacular “lone wolf” attacks, like the Oklahoma City federal building bombing in 1995, the mass murder at a Charleston church in 2015 and the Pittsburgh synagogue shooting in 2018. But these people are not alone.

Most far-right extremists are part of larger extremist communities, communicating by social media and distributing posts and manifestos.

Their messages speak of fear that one day, whites may be outnumbered by nonwhites in the U.S., and the idea that there is a Jewish-led plot to destroy the white race. In response, they prepare for a war between whites and nonwhites.

[Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter.]

Thinking of these extremists as loners risks missing the complexity of their networks, which brought as many as 13 alleged plotters together in the planning to kidnap Michigan’s governor.

Together, these misconceptions about far-right extremist individuals and groups can lead Americans to underestimate the dire threat they pose to the public. Understanding them, by contrast, can help people and experts alike address the danger, as the election – and its aftermath – unfolds.![]()

Alexander Hinton, Distinguished Professor of Anthropology; Director, Center for the Study of Genocide and Human Rights, Rutgers University – Newark

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

================================================================

Alecto, Megaera, and Tisiphone, I listened to (Derrick Wang’s opera) Scalia/Ginsburg this afternoon. I hope that the time when people with such disagreements could be friends is not over, though I fear it is – it has become too clear that politics are not just politics, that morality is a huge factor in political policy and decisions. We shall see. And I know we shall not stop working for a better world.

The Furies and I will be back.