Experts in autocracies have pointed out that it is, unfortunately, easy to slip into normalizing the tyrant, hence it is important to hang on to outrage. These incidents which seem to call for the efforts of the Greek Furies (Erinyes) to come and deal with them will, I hope, help with that. As a reminder, though no one really knows how many there were supposed to be, the three names we have are Alecto, Megaera, and Tisiphone. These roughly translate as “unceasing,” “grudging,” and “vengeful destruction.”

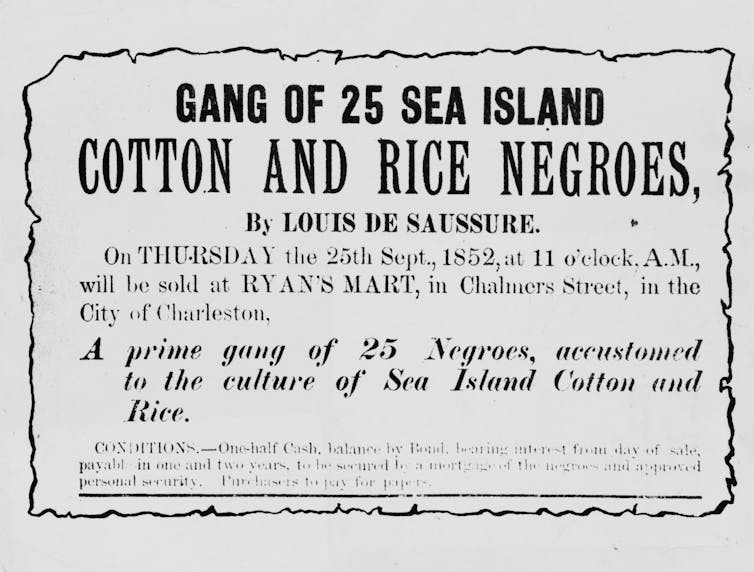

With Labor Day upon us, and after a summer during which we have seen a fair number of strikes, perhaps it’s time to look at history and to realize that what seems like a lot of strikes to us only seems so because for the last forty-plus years conservatives have worked hard to cripple labor, especally labor unions. The NLRB’s new ruling, which will help to disempower union busters. will help turn that around. But we re still a long way from the “Look for theUnion label” days.

==============================================================

Waves of strikes rippling across the US seem big, but the total number of Americans walking off the job remains historically low

AP Photo

Judith Stepan-Norris, University of California, Irvine and Jasmine Kerrissey, UMass Amherst

More than 323,000 workers – including nurses, actors, screenwriters, hotel cleaners and restaurant servers – walked off their jobs during the first eight months of 2023. Hundreds of thousands of the employees of delivery giant UPS would have gone on strike, too, had they not reached a last-minute agreement. And nearly 150,000 autoworkers may go on a strike of historic proportions in mid-September if the United Autoworkers Union and General Motors, Ford and Stellantis – the company that includes Chrysler – don’t agree on a new contract soon.

This crescendo of labor actions follows a relative lull in U.S. strikes and a decline in union membership that began in the 1970s. Today’s strikes may seem unprecedented, especially if you’re under 50. While this wave constitutes a significant change following decades of unions’ losing ground, it’s far from unprecedented.

We’re sociologists who study the history of U.S. labor movements. In our new book, “Union Booms and Busts,” we explore the reasons for swings in the share of working Americans in unions between 1900 and 2015.

We see the rising number of strikes today as a sign that the balance of power between workers and employers, which has been tilted toward employers for nearly a half-century, is beginning to shift.

Apu Gomes/Getty Images

Millions on strike

The number of U.S. workers who go on strike in a given year varies greatly but generally follows broader trends. After World War II ended, through 1981, between 1 million and 4 million Americans went on strike annually. By 1990, that number had plummeted. In some years, it fell below 100,000.

Workers by that point were clearly on the defensive for several reasons.

One dramatic turning point was the showdown between President Ronald Reagan and the country’s air traffic controllers, which culminated in a 1981 strike by their union – the Professional Air Traffic Controllers Organization. Like many public workers, air traffic controllers did not have the right to strike, but they called one anyway because of safety concerns and other reasons. Reagan depicted the union as disloyal and ordered that all of PATCO’s striking members be fired. The government turned to supervisors and military controllers as their replacements and decertified the union.

That episode sent a strong message to employers that permanently replacing striking workers in certain situations would be tolerated.

There were also many court rulings and new laws that favored big business over labor rights. These included the passage of so-called right-to-work laws that provide union representation to nonunion members in union workplaces – without requiring the payment of union dues. Many conservative states, like South Dakota and Mississippi, have these laws on the books, along with states with more liberal voters – such as Wisconsin.

As union membership plunged from 34.2% of the labor force in 1945 to around 10% in 2010, workers became less likely to go on strike.

Wages kept up with productivity gains when unions were stronger than they are today. Wages increased 91.3% as productivity grew by 96.7% between 1948 and 1973. That changed once union membership began to tumble. Wages stagnated from 1973 to 2013, rising only 9.2% even as productivity grew by 74.4%.

Prime conditions

In general, strikes grow more common when economic conditions change in ways that empower workers. That’s especially true with the tight labor markets and high inflation seen in the U.S. in recent years.

When there are fewer candidates available for every open job and prices are rising, workers become bolder in their demands for higher wages and benefits.

Political and legal factors can play a role, too.

In the 1930s, President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal enhanced unions’ ability to organize. During World War II, unions agreed to a no-strike pledge – although some workers continued to go on strike.

The number of U.S. workers who went on strike peaked in 1946, a year after the war ended. Conditions were ripe for labor actions at that point for several reasons. The economy was no longer so dedicated to supplying the military, pro-union New Deal legislation was still intact and wartime strike restrictions were lifted.

In contrast, Reagan’s crushing of the PATCO strike gave employers a green light to permanently replace striking workers in situations in which doing that was legal.

Likewise, as we describe in our book, employers can take many steps to discourage strikes. But labor organizers can sometimes overcome management’s resistance with creative strategies.

New economic equations

Between 1983 and 2022, the share of U.S. workers who belonged to unions fell by half, from 20.1% to 10.1%. The COVID-19 pandemic didn’t reverse that decline, but it did change the balance of power between employers and workers in other ways.

The “great resignation,” a surge in the number of workers quitting their jobs during the pandemic, now seems to be over, or at least cooling down. The number of unemployed people for every job opening reached 4.9 in April 2020, plummeted to 0.5 in December 2021, and has remained low ever since.

Meanwhile, many workers have become more dissatisfied with their wages. The strikes by teachers that ramped up in 2018 responded to that frustration. U.S. inflation, which soared to 8% in 2022, has eroded workers’ purchasing power while company profits and economic inequality have continued to soar.

Technological breakthroughs that leave workers behind are also contributing to today’s strikes, as they did in other periods.

We’ve studied the role technology played in the printers’ strikes of the 1890s following the introduction of the linotype machine, which reduced the need for skilled workers, and the longshoremen strike of 1971, which was spurred by a drastic workforce reduction brought about by the introduction of shipping containers to transport cargo.

Those are among countless precedents for what’s happening now with actors and screenwriters. Their strikes hinge on the financial implications of streaming in film and television and artificial intelligence in the production of movies and shows.

Working conditions, including health and safety concerns and time off, have also been at the root of many recent strikes.

Health care workers, for example, are going on strike over safe staffing levels. In 2022, rail workers voted to strike over sick days and time off, they but were blocked from walking off the job by a U.S. Senate vote and President Joe Biden’s signature.

Time and again, when the conditions have been right, U.S. workers have gone on strike and won. Sometimes more strikes have followed, in waves that can transform workers’ lives. But it’s too early to know how big this wave will become.![]()

Judith Stepan-Norris, Professor Emerita of Sociology, University of California, Irvine and Jasmine Kerrissey, Associate Professor of Sociology; Director of the Labor Center, UMass Amherst

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

==============================================================

Alecto, Megaera, and Tisiphone, it’s not hard to see why Americans who regard life itself as a zero-sum game would be distrustful of unions (and unwilling to pay dues). What’s less easy to see is how so many Americans – citizens of a country founded on the common good – regard life as a zero-sum game. Sure, they’ve been suckered into that belief, and conservatives are certainly doing their best to make it true, because people’s belief in it benefits only the wealthy. But we didnt always think that way. Today’s authors tend to answer that question. However, the bigger question of how do we get back to sanity remains.

The Furies and I will be back.