Experts in autocracies have pointed out that it is, unfortunately, easy to slip into normalizing the tyrant, hence it is important to hang on to outrage. These incidents which seem to call for the efforts of the Greek Furies (Erinyes) to come and deal with them will, I hope, help with that. As a reminder, though no one really knows how many there were supposed to be, the three names we have are Alecto, Megaera, and Tisiphone. These roughly translate as “unceasing,” “grudging,” and “vengeful destruction.”

If there is anything we need right now, it is ways to talk about America, about politics, about conspiracies, about nearly everything, in ways which do not lead to violence but do lead to the proliferation of truth. Ben Franklin felt he had found this in the Socratic method – and certainly that method has been known to work for millennia. Which may be related to the fact that it is in contradiction to the modern American stereotype (probably a wider stereotype than just in America) of the “alpha male,” the “manly man,” the “winner.” (Slightly off topic, but the “alpha male” concept, thought to be from the wild, was actually drawn from observations of animals in captivity. In the wild, they act quite differently.)

But, if anyone can reframe the Socratic method so as to sell it to modern Americans, it would be Ben Franklin. So let’s give him a shot at it.

================================================================

Talking politics in 2021: Lessons on humility and truth-seeking from Benjamin Franklin

Rozbike/Wikipedia, CC BY-SA

Mark Canada, Indiana University

The previous year in the United States was a turbulent one, filled with political strife, protests over racism and a devastating pandemic. Underlying all three has been a pervasive political polarization, made worse by a breakdown in civic – and civil – discourse, not only on Capitol Hill, but around the nation.

In a new year, with a new president and a new Congress, there appears to be opportunity. Americans, starting with the president, are talking about turning away from the division of the recent past and choosing a different direction: talking civilly and productively about the problems the country faces.

But how to do that? As a literary scholar, I appreciate the power of carefully crafted language, and I believe that Americans – from those in government to those around the dinner table – could take a lesson from one of this nation’s founders and greatest communicators: Benjamin Franklin.

From ‘positive Argumentation’ to ‘modest Diffidence’

Before he achieved fame as a statesman, scientist and diplomat, Franklin, who was born in 1706 and died in 1790, made his living in Philadelphia from words – as a printer, journalist and essayist.

Having worked early in his life in Boston for his brother James, a fiery journalist, he knew the kind of war that could be waged with words and had even made a hobby of debating with a young friend.

“We sometimes disputed,” Franklin recalled in his autobiography, “and very fond we were of Argument, & very desirous of confuting one another.”

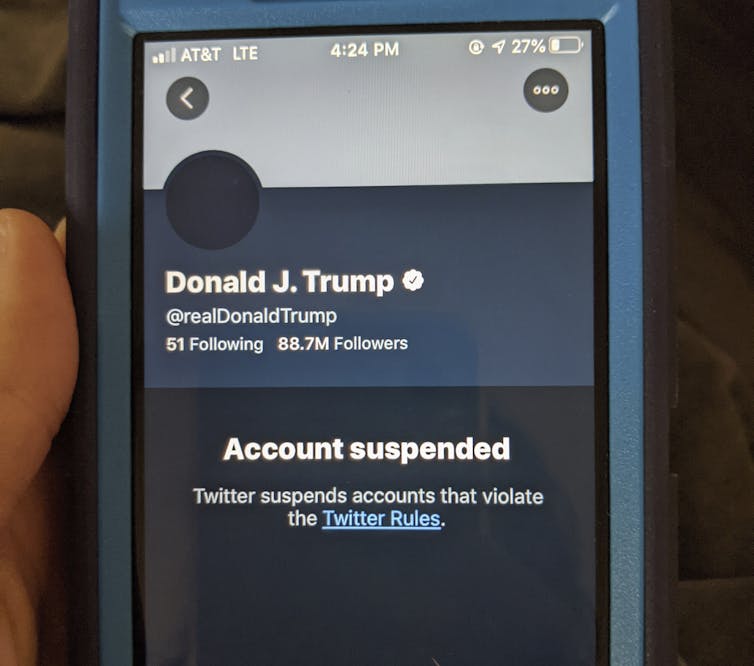

David McNew/Getty Images

Everything changed for Franklin, however, after he came across some examples of Socratic dialogue, in which questions figure prominently. “I was charm’d with it,” Franklin wrote, “adopted it, dropt my abrupt Contradiction, and positive Argumentation, and put on the humble Enquirer & Doubter.”

The inspired Franklin eventually changed his entire manner of discourse, communicating “in terms of modest Diffidence” instead of positive assertion, dropping words such as “certainly” and “undoubtedly” and substituting “I should think it so or so” and “it is so, if I am not mistaken.”

After all, Franklin wrote, “a positive, assuming manner” tends to turn off an audience and thus undermines one’s own intentions.

Such positive assertion can interfere with the exchange of valuable information. “If you wish information and improvement from the knowledge of others,” Franklin wrote, “and yet at the same time express yourself as firmly fix’d in your present opinions, modest, sensible men, who do not love disputation, will probably leave you undisturbed in the possession of your error.”

In 2021, replacing positive assertions in conversations with some “terms of modest Diffidence” just might lead to exchanges that are not only more civil, but also more productive.

Pursuing truth, not victory

More important than modest expression is actual intellectual humility, and here again Franklin’s example is instructive. Even before he turned his inquiring mind to groundbreaking discoveries in electricity, he showed a scientist’s dedication to open, objective investigation with only truth as its object.

In 1727, when he was still in his early 20s, he founded a group called the Junto. Members, including a number of tradesmen like Franklin, took up political, philosophical and other questions such as “Does the Importation of Servants increase or advance the Wealth of our Country?” and “Wherein consists the Happiness of a rational Creature?”

The goal of these discussions, as Franklin explained, was not victory – as it apparently had been for Franklin and his friend years earlier – but something far more valuable for all concerned. Franklin explained that the discussions were to take place “in the sincere Spirit of Enquiry after Truth, without fondness for Dispute, or Desire of Victory.” Anyone who spoke too confidently or contentiously had to pay a small fine.

This preference for pursuing truth over seeking victory found expression in a question that initiates were required to answer: “Do you love and pursue truth for its own sake?” Franklin did, and the results speak for themselves.

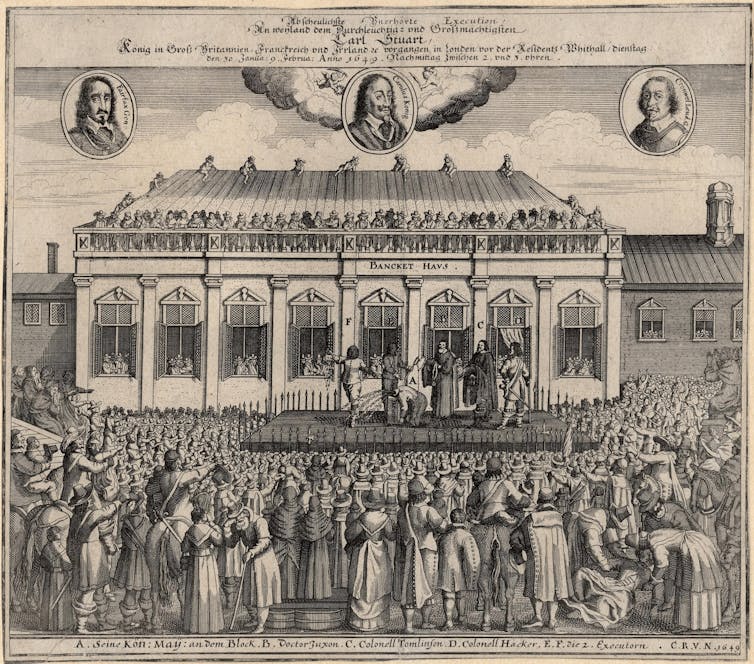

Education Images/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Franklin also had a prescient understanding of biases that color humans’ understanding of reality.

Today, scientists have shown that people are susceptible to mere exposure effect, a preference for information we have encountered multiple times and confirmation bias, an inclination toward information that aligns with a person’s current beliefs. In an essay he published in the 1730s, Franklin wrote of the effect of “Prevailing Opinions” on the individual mind and observed, “A Man can hardly forbear wishing those Things to be true and right, which he apprehends would be for his Conveniency to find so.” He added, “That Man only, who is ready to change his Mind upon proper Conviction, is in the Way to come at the Knowledge of Truth.”

Franklin lived up to this principle. In 1751, he published an essay expressing reprehensible, racist views that were all too common in his era. Years later, however, he helped found schools to educate black children and, after visiting one, saw that the students were equal to white children in their ability to learn.

He wound up changing not only his mind but also his essay when he reprinted it almost two decades later, changing the passage that said that most slaves were thieves “by Nature” to say that they were thieves because of slavery.

[Like what you’ve read? Want more? Sign up for The Conversation’s daily newsletter.]

Near the end of his life, Franklin became president of the Pennsylvania Society for Promoting the Abolition of Slavery and submitted to Congress a petition to abolish slavery and end the slave trade.

‘Obliged by better information … to change opinions’

At the Constitutional Convention of 1787, Franklin expressed his belief in intellectual humility. As James Madison recorded his words, Franklin said, “For having lived long, I have experienced many instances of being obliged by better information, or fuller consideration, to change opinions even on important subjects, which I once thought right, but found to be otherwise.”

“It is therefore that the older I grow,” he added, “the more apt I am to doubt my own judgment, and to pay more respect to the judgment of others.”

Near the end of the speech, he implored others to adopt this same humility: “On the whole, Sir, I can not help expressing a wish that every member of the Convention who may still have objections to it, would with me, on this occasion doubt a little of his own infallibility, and to make manifest our unanimity, put his name to this instrument.”

As these words and experience testify, political polarization and dispute are nothing new. But Franklin managed to rise above the discord, biases and close-mindedness that are common in any era.

He spoke and wrote in ways that, if taken up now, could begin to erode the polarization of the current era: with modesty, diffidence, sincere consideration of others’ positions, doubt in his own infallibility and love of truth for its own sake.![]()

Mark Canada, Executive Vice Chancellor for Academic Affairs, Indiana University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

================================================================

Alecto, Megaera, and Tisiphone, the Socratic method requires real self-control. Real humility also does not hurt. It’s just as difficult for Democrats as it is for Republicans, or anyone else, to refrain from boldly asserting that truth is truth when, in fact, it f’ing well is. But that doesn’t work very well.

Admittedly, the Socratic method does not adapt well to sound bytes, memes, or throwing shade. But, you know, those don’t work either. The Socratic method does work best in a one-on-one conversation, though there may also be a crowd of listeners, as long as they are actually listening. It couldn’t hurt to at least attempt to try it out.

The Furies and I will be back.