Experts in autocracies have pointed out that it is, unfortunately, easy to slip into normalizing the tyrant, hence it is important to hang on to outrage. These incidents which seem to call for the efforts of the Greek Furies (Erinyes) to come and deal with them will, I hope, help with that. As a reminder, though no one really knows how many there were supposed to be, the three names we have are Alecto, Megaera, and Tisiphone. These roughly translate as “unceasing,” “grudging,” and “vengeful destruction.”

We never used to, and mostly still don’t, think of winter as tornado season. (We also don’t think of earthquakes in the eastern United Sttes, ot hurricanes reaching New Yor, or sea level rise.) But it looks as though we are going to have to start thinking about all of these things.

Of course there is a lot science still doesn’t know. One limitation of science is that in order to actually study something – as opposed to making a model, which is what climate scientists have been doing – that something has to actually exist. And I guarantee there are many things we undoubtedly hope we will never have to know, if they don’t make it from model to reality. But winter tornadoes are not one of those things. They are here.

================================================================

Tornadoes and climate change: What a warming world means for deadly twisters and the type of storms that spawn them

Mike Coniglio/NOAA/NSSL

John Allen, Central Michigan University

The deadly tornado outbreak that tore through communities from Arkansas to Illinois on the night of Dec. 10-11, 2021, was so unusual in its duration and strength, particularly for December, that a lot of people including the U.S. president are asking what role climate change might have played – and whether tornadoes will become more common in a warming world.

Both questions are easier asked than answered, but research is offering new clues.

I’m an atmospheric scientist who studies severe convective storms like tornadoes and the influences of climate change. Here’s what scientific research shows so far.

Climate models can’t see tornadoes yet – but they can recognize tornado conditions

To understand how rising global temperatures will affect the climate in the future, scientists use complex computer models that characterize the whole Earth system, from the Sun’s energy streaming in to how the soil responds and everything in between, year to year and season to season. These models solve millions of equations on a global scale. Each calculation adds up, requiring far more computing power than a desktop computer can handle.

To project how Earth’s climate will change through the end of the century, we currently have to use a broad scale. Think of it like the zoom function on a camera looking at a distant mountain. You can see the forest, but individual trees are harder to make out, and a pine cone in one of those trees is too tiny to see even when you blow up the image. With climate models, the smaller the object, the harder it is to see.

Tornadoes and the severe storms that create them are far below the typical scale that climate models can predict.

What we can do instead is look at the large-scale ingredients that make conditions ripe for tornadoes to form.

Mike Coniglio/NOAA NSSL

Two key ingredients for severe storms are (1) energy driven by warm, moist air promoting strong updrafts, and (2) changing wind speed and direction, known as wind shear, which allows storms to become stronger and longer-lived. A third ingredient, which is harder to identify, is a trigger to get storms to form, such as a really hot day, or perhaps a cold front. Without this ingredient, not every favorable environment leads to severe storms or tornadoes, but the first two conditions still make severe storms more likely.

By using these ingredients to characterize the likelihood of severe storms and tornadoes forming, climate models can tell us something about the changing risk.

How storm conditions are likely to change

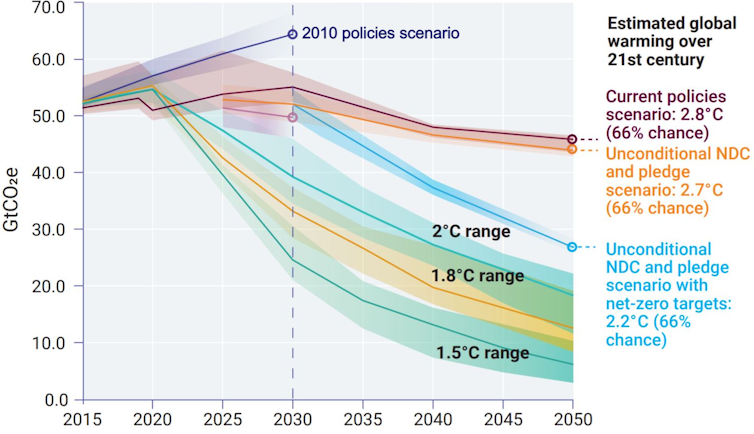

Climate model projections for the United States suggest that the overall likelihood of favorable ingredients for severe storms will increase by the end of the 21st century. The main reason is that warming temperatures accompanied by increasing moisture in the atmosphere increases the potential for strong updrafts.

Rising global temperatures are driving significant changes for seasons that we traditionally think of as rarely producing severe weather. Stronger increases in warm humid air in fall, winter and early spring mean there will be more days with favorable severe thunderstorm environments – and when these storms occur, they have the potential for greater intensity.

What studies show about frequency and intensity

Over smaller areas, we can simulate thunderstorms in these future climates, which gets us closer to answering whether severe storms will form. Several studies have modeled changes to the frequency of intense storms to better understand this change to the environment.

We are already seeing evidence in the past few decades of shifts toward conditions more favorable for severe storms in the cooler seasons, while the summertime likelihood of storms forming is decreasing.

Scott Olson/Getty Images

For tornadoes, things get trickier. Even in an otherwise spot-on forecast for the next day, there is no guarantee that a tornado will form. Only a small fraction of the storms produced in a favorable environment will produce a tornado at all.

Several simulations have explored what would happen if a tornado outbreak or a tornado-producing storm occurred at different levels of global warming. Projections suggest that stronger, tornado-producing storms may be more likely as global temperatures rise, though strengthened less than we might expect from the increase in available energy.

The impact of 1 degree of warming

Much of what we know about how a warming climate influences severe storms and tornadoes is regional, chiefly in the United States. Not all regions around the globe will see changes to severe storm environments at the same rate.

In a recent study, colleagues and I found that the rate of increase in severe storm environments will be greater in the Northern Hemisphere, and that it increases more at higher latitudes. In the United States, our research suggests that for each 1 degree Celsius (1.8 F) that the temperatures rises, a 14-25% increase in favorable environments is likely in spring, fall and winter, with the greatest increase in winter. This is driven predominantly by the increasing energy available due to higher temperatures. Keep in mind that this is about favorable environments, not necessarily tornadoes.

What does this say about December’s tornadoes?

To answer whether climate change influenced the likelihood or intensity of tornadoes in the December 2021 outbreak, it remains difficult to attribute any single event like this one to climate change. Shorter-term influences like the El Niño-Southern Oscillation may also complicate the picture.

There are certainly signals pointing in the direction of a stormier future, but how this manifests for tornadoes is an open area of research.

[Over 140,000 readers rely on The Conversation’s newsletters to understand the world. Sign up today.]![]()

John Allen, Associate Professor of Meteorology, Central Michigan University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

================================================================

Alecto, Megaera, and Tisiphone, this is an article aimed at general audiences. In the comments, another scientist addresses another aspect, and Professor Allen replaies that that was omitted deliberately to keep the article clearer for the general reader. In actuality, there are many factors which affect, say, tornadoes. As a general reader myself, I would ask something mike, “Given other contributing factors such as El Niño-Southern Oscillation, if surface warming were not present, would this tornado have happened when it did,. the way it did?” And I suspect the answer to that is “No.” But even if it’s only “Maybe,” I don’t understand why we still continue to take such chances with our and other people’s lives.

The Furies and I will be back.