Experts in autocracies have pointed out that it is, unfortunately, easy to slip into normalizing the tyrant, hence it is important to hang on to outrage. These incidents which seem to call for the efforts of the Greek Furies (Erinyes) to come and deal with them will, I hope, help with that. As a reminder, though no one really knows how many there were supposed to be, the three names we have are Alecto, Megaera, and Tisiphone. These roughly translate as “unceasing,” “grudging,” and “vengeful destruction.”

Yes, I realize I just wrote about rivers last week. But rivers – water – like butterflies but even more so – are foundational to our survivsl at any time, and in the face of climate change it really is not possib;e to overestimate their importance. And rivers depend on watersheds. And watersheds, apparently, are, to put it mildly, poorly understood.

New Mexico – and I include in that former New Mexicans who have taken their knowledge elsewhere – is on the cutting edge when it comes to stream gauges and other technology to understand water flow. This probably should not be a surprise. Nobody knows water flow like people who live in areas which are essentially deserts, and especially people who have grown up in those areas. I’ve lived in high desert, but I didn’t grow up in one, and I assure you the phrase “stream gauge placement bias” would never have occurred to me, let alone passed my lips until reading this.

==============================================================

How much do we know about our watersheds? New study says gaps in knowledge exist because of ‘bias’ in stream gauge placement

Corey Krabbenhoft saw the ebbs and flows of New Mexico’s rivers growing up in Albuquerque. From that experience, she knew how many of the waterways in the state only flow at certain times of the year.

As a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Buffalo, she is the lead author on a new paper published in the journal Nature Sustainability that looks at stream gauges, particularly in what the authors call “bias” in placement.

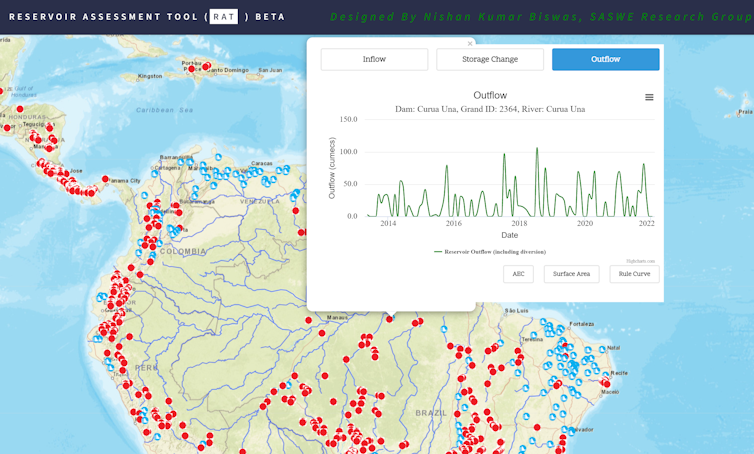

Krabbenhoft explained that the study doesn’t focus on where the stream gauges are located, but rather what types of rivers are represented globally when it comes to monitoring with gauges. This paper documented that ephemeral waters, headwaters and waterways in protected areas like wilderness areas are less likely to have stream gauges on them, which can lead to a gap in knowledge about how the river systems work.

In contrast, larger rivers that often have dams on them regulating the flows and usually pass through more populated areas are more likely to have these gauges.

In the introduction, the study authors state that this “weakens our ability to understand critical hydrologic processes and make informed water-management and policy decisions.”

Hydrologist George Allen, an associate professor at Texas A&M University and an author of the paper, said the team of researchers used a system called the Global Reach-level A priori Discharge Estimates for Surface Water and Ocean Topography (GRADES) dataset, which gathers publicly-available data. He said this does have limitations. While the United States tends to provide its data, other countries are less transparent.

The study traces its roots to a meeting in 2019 in New Mexico. During the meeting, the team decided to look into topics like water gauges.

Allen explained that the National Science Foundation funded a research coordination network to focus on dry rivers. This team had a diverse set of backgrounds including hydrologists like Allen and ecologists like Krabbenhoft. The team spent a handful of days in New Mexico talking about science and came up with several research ideas, including the location of stream gauges.

Krabbenhoft said the southwest United States is arid and many of the rivers are underrepresented when it comes to gauges.

This means not as much is known about the smaller rivers in the arid southwest despite the fact that those rivers play an important role in the ecosystem health and hydrology.

Map of river basin areas throughout the United States

Krabbenhoft said if all the information is being gathered downstream rather than upstream in areas like headwaters, it limits the ability to predict what’s going to happen in the watershed and to respond to those changes.

How did we get here?

The study authors describe this bias as inadvertent and say that it arose from the installation of gauges being dictated by national and local planning.

New Mexico holds a special distinction in the United States when it comes to water management. In 1889, the U.S. Geological Survey installed its first gauge on the Rio Grande at the town of Embudo, between Española and Taos. The Embudo gauge was installed in part as a training initiative that allowed hydrographers to develop stream gauging techniques.

It has since become an important gauge to measure the flows of the Rio Grande.

As interstate compacts were signed to ensure distribution of water among states, stream gauges began to play a critical role in meeting those goals.

Chris Stageman with the New Mexico Interstate Stream Commission said New Mexico’s gauges have been used to collect measurements that ensure compliance with compacts like the Rio Grande Compact and for making sure that different projects are in compliance with environmental permits.

For example, gauges help water managers to track how much water in the Rio Grande is considered native, meaning it originated in the drainages that feed the river, and how much of it is non-native, meaning it was moved into the Rio Grande as part of the San Juan-Chama Project. This is important because the water from the San Juan River falls under the Colorado River Compact while native Rio Grande water is subject to the Rio Grande Compact. Downstream users like Texas are not entitled to the San Juan water.

The gauges also ensure that New Mexico is meeting its commitments to protecting endangered species and help with compliance in various permits.

What does the gauge network look like in New Mexico?

In New Mexico, various entities have steam gauges, which tend to be located along major rivers. The U.S. Geological Survey, the Elephant Butte Irrigation District, the New Mexico Office of the State Engineer and the U.S. Bureau of Reclamation all have installed gauges.

The majority of gauges in New Mexico are operated by the Water Science Center, which is based in Albuquerque.

Stageman said New Mexico, in his opinion, has a good network of steam gauges, however, he said “we can always do better.”

One area that he said could use additional monitors is irrigation return flows.

“We have fairly good gauging on the diversions from the river. But we don’t have a really good system of measuring the return flows to the river,” he said.

Stageman said the Office of the State Engineer also runs quite a few gauges measuring diversions off of the main river systems.

“That’s important especially in these times of water shortages,” he said. “It’s important for ensuring that people aren’t taking too much water.”

He said those gauges also help ensure the water is fairly distributed and reduce conflict.

He said, from a compact and environmental compliance perspective, New Mexico’s network of stream gauges provides adequate coverage of the state. There are gauges on the Rio Grande, the San Juan River, the Pecos River, the Gila River and the Canadian River as well as other waterways in the state. But, from other perspectives, such as environmental monitoring, he agreed with the authors of the paper.

Stacy Timmons, associate director of hydrogeology programs at the New Mexico Bureau of Geology, oversees the implementation of the state’s Water Data Act, which was passed in 2019.

Whether New Mexico has enough stream gauges comes down to the question of for what purpose, Stacy Timmons said. Timmons oversees the implementation of the state’s Water Data Act. In terms of basic water management, she said New Mexico’s network meets the needs.

But, if it comes to answering more in-depth questions like whether a river is gaining water or losing water at a specific point, Timmons said there isn’t enough data to answer that in many parts of the state.

She said the high population areas do tend to have good monitoring systems in place.

With drought becoming an increasingly more pressing reality in New Mexico, Timmons compared the water monitoring data to a fuel gauge in a car. She said if she’s driving along and her fuel gauge is showing the tank is close to empty, she will be checking it more frequently.

“I think as we face water scarcity, we need to have quick access to that data so we can make our decisions with that context and information,” she said.

The Water Data Act aims to make it easier for entities in New Mexico who monitor water data, such as stream gauges or reservoir levels, to share that information by aggregating it at a central location. This data will then be available to anyone who is interested in it.

“In New Mexico, we need to wake up to the reality of our water scarce future and do all we can to help the agencies that help us keep an eye on water resources and manage it carefully,” she said.

What are some limiting factors in stream gauge installation?

One of the biggest limiting factors in the number of gauges is costs. Stageman said the costs don’t end once the gauge is installed. Maintenance is required to keep them operational.

“We have to go out there and physically measure the water to make sure that the gauges are acting properly,” he said. “And our staff does that as well as the USGS staff. We kind of collaborate on all of that.”

The USGS has more than 8,000 streamgages nationwide and it can be expensive to keep those going. In recent years, the agency has retired gages. In the last 13 months, a lack of funding has led the USGS to shut down four streamgages, including one in New Mexico, according to a USGS website that tracks discontinued and endangered streamgages. This streamgage was located on the Rio Grande near White Rock above the Buckman Diversion. It operated for three years.

Timmons said another challenge with New Mexico’s ephemeral waters is the substrate. She said the streams tend to change course. The stream gauges would have to be moved if the waterway shifted location and that is not an easy task.

The sandy substrate that is common in New Mexico also limits where stream gauges can be placed, Stageman said.

He said if a gauge is placed below a wash that flows intermittently and carries a lot of sediment when it runs, that could wreak havoc on the equipment.

Why is this data important?

Allen said most rivers in the world are not large.

“They’re rivers that go dry, that are small,” he said. “And if we want to understand how climate change and land use are changing our freshwater resources, it’s important to have observations across all kinds of rivers, including the most common types of rivers, which are these small rivers.”

He said gauges can help track trends in river flows, including historical flows compared to current flows.

There are other methods that can be used to monitor rivers, Allen said. For example, he has looked at satellite data as a way of tracking changes in the rivers. But this doesn’t provide the same level of details as the river gauge. Allen said gauges provide a continuous stream of data while satellites might update every few days as the satellite passes over that location.

With climate change leading to aridification and drought, water management is becoming even more critical than ever before.

“Understanding how the drought is affecting water resources in New Mexico really depends on our ability to monitor the surface water resources,” Allen said.

==============================================================

Alecto, Megaera, and Tisiphone, “enough for basic water management” now is good, but not good enough for basic water management tomorrow, and not good enough to predict potential future weak spots. There are seven states in the Colorado River Compact and three in the Rio Grande compact, and Colorado and New Mexico are in both compacts, which kind of makes us ground zero. If any of us is going to survive, we need to know about rivers and watersheds and water in general than we now do.

(If you want a soundtrack, here is one – a portrait in music of a river from little trickles at the mountain watershed all the way down to the mighty river that enters the ocean (and observing things and people along the way)

The Furies and I will be back.

![]()