Experts in autocracies have pointed out that it is, unfortunately, easy to slip into normalizing the tyrant, hence it is important to hang on to outrage. These incidents which seem to call for the efforts of the Greek Furies (Erinyes) to come and deal with them will, I hope, help with that. As a reminder, though no one really knows how many there were supposed to be, the three names we have are Alecto, Megaera, and Tisiphone. These roughly translate as “unceasing,” “grudging,” and “vengeful destruction.”

I was going to say something like, “I’m sorry, but it really angers me that…” but the truth is I’m not sorry at all. It makes me very angry to see white snowflakes cmpaining about trauma for them and particularly for their kids just thinking about white ill treatment of black people, when the real trauma is being suffered by black people, 24 hours a day, seven days a week, And I will not apologize for being angry angry about that. This article, nominally about how people cope, is in some ways more about the quantity and the nature of what black people have to cope with. And God forbid they should say anything to make Wypipo uncomfortable! Well, I believe in comforting the afflicted, but also in afflicting the comfortable. Comforting the afflicted helps. But only afflicting the comfortable can bring about lasting change.

==============================================================

How Black communities cope with trauma triggered by police brutality

Lucy Garrett/Getty Images

Deion Scott Hawkins, Emerson College

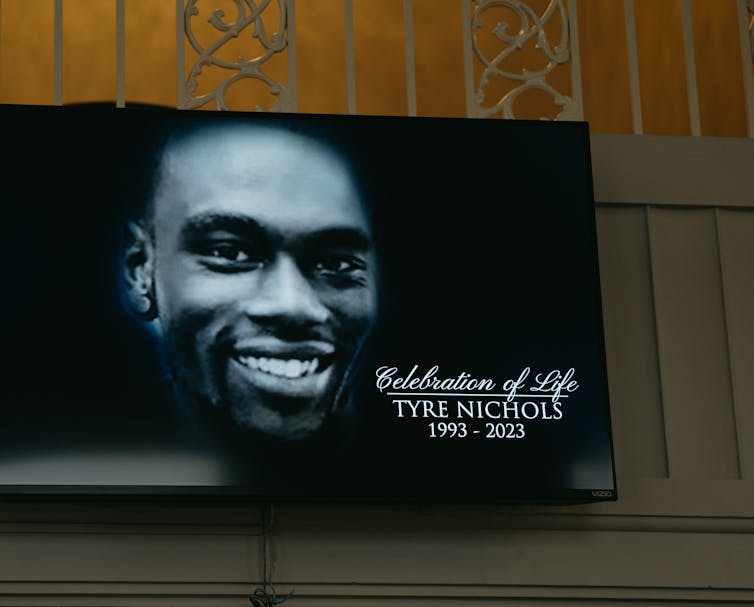

The release of footage showing the brutal beating of Tyre Nichols by Memphis police and protests in Atlanta have renewed public debate on the issues of police brutality and police reform.

For some people, seeing is believing, and the circulation of videos documenting police violence is valued as a tool of accountability.

But for many in the Black community, which studies show is disproportionately affected by police brutality, viewing videos of and having conversations about police violence can have several adverse effects, including psychological distress and trauma.

What is trauma?

The American Psychological Association defines trauma as “any disturbing experience that results in significant fear, helplessness, dissociation, confusion, or other disruptive feelings intense enough to have a long-lasting negative effect on a person’s attitudes, behavior, and other aspects of functioning.”

In her seminal book “Trauma and Recovery: The Aftermath of Violence – From Domestic Abuse to Political Terror,” published in 1992, Dr. Judith Lewis Herman notes that encountering a traumatic event permanently alters one’s perceptions of safety.

To prepare for a threat, these individuals develop intense feelings of fear and anger.

These changes in emotional state are usually biological, as shifts in attention, perception and emotion are normal physiological reactions to a perceived threat.

This is known as our “fight or flight response.”

Trauma can manifest itself in various ways. For example, on some occasions, traumatic events are known to lead to feelings of depression and intense sadness and episodes of

helplessness.

Additionally, trauma is known to increase one’s state of hypervigilance, or the elevated state of constantly assessing potential threats in the area. This state of elevated alertness often creates anxiety around dying and can have physiological impacts on the body, such as sweating and elevated heart rate.

Police brutality and Black trauma

As a critical scholar and researcher, I use trauma-informed interview techniques to better understand the intersections of police brutality and mental health in the Black community. My research

focuses on those most affected, and that research highlights the human experience.

There is always a face behind the statistic.

Thus, my work typically uses critical race theory, as it focuses on the perspectives of marginalized people. For example, my study published in the Journal of Health Communication explored how stories of police brutality are circulated within the Black community and how these stories affect mental health.

Through dozens of interviews, I discovered three key ways in which trauma is triggered by incidents of police brutality that often appear in Black communities.

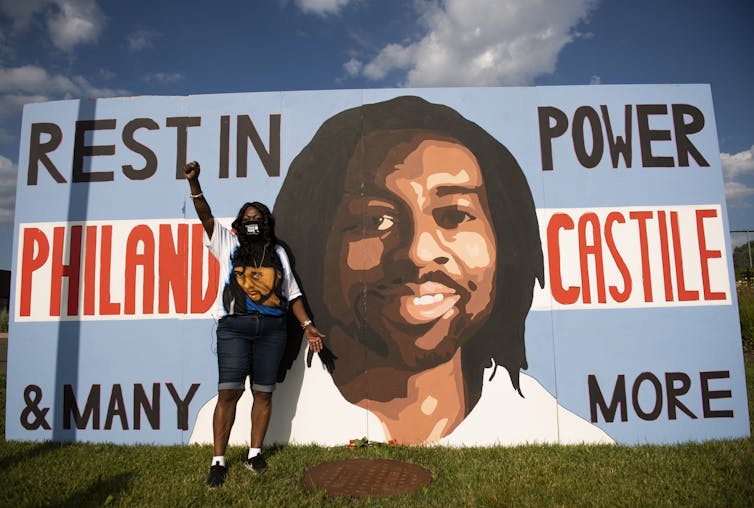

Stephen Maturen/Getty Images

Intense sadness, hypervigilance and sense of helplessness

The excerpts below are direct quotations from members of the Black community whom I interviewed as part of a larger research project. This study was conducted in Washington, D.C., in 2018, but its findings are still relevant, as it reveals how police brutality directly fuels trauma in the Black community.

Because of research protections and protocol, pseudonyms are used, and no other identifying information can be published.

1. Intense sadness

When asked about feelings after viewing videos or images of brutality, every interviewee indicated intense sadness as the primary emotion. This sadness often affected how individuals went about their day, especially work-related activities.

Darius

I remember I walked into work, face cut up and people were like, “What’s wrong? What happened?” I told them I had been in a fight. But really, I had been beat up by a police officer who assumed I was someone else. I appreciated them asking me if I was OK, but I wasn’t really comfortable telling them, you know? We had previous conversations that let me know they didn’t really think Black lives mattered. After Philando, I had to take a sick day to recover. That’s how sad I was, man.

Chanelle

Philando Castile. I was rrreealllly sad. Philando was the boiling point. I cracked. I literally had to leave my desk at work and take a break. When I came back, my white co-workers told me I was overreacting because I didn’t know him, which pissed me off. What they don’t get is that Philando could be anyone in my family. It’s not just Philando, it’s that I fear my brothers could be shot in cold blood at any moment. That’s why I was so damn sad.

2. Hypervigilance

Interviewees also discussed their chronic fear of dying at the hands of law enforcement. In turn, this fear prompts a permanent state of hypervigilance or hyperalertness; many members of the Black community constantly feel they are going to die if they encounter a police officer.

Mary

Whenever I see cops, I tense up. One time, cops pulled up to me when I was in a car and my friend looked at me with the straightest face and said, “One of us is about to die.” I was so shocked, and I said, “That’s not funny.” But he was serious. He really thought one of us was going to die.

Jason Armond/Los Angeles Times via Getty Images

Luke

There is not a single time where I can sit in a car and hear a siren or see a cop light flash, that I’m not fearful. I imagine it’s like what soldiers feel when they hear anything that sounds like a bomb. When I hear sirens, I start to look around and hope that someone else is around. Because, if I were to get shot, I would want someone to be able to tell the truth. People are straight up dropping at the hands of police. I never want to be in that situation.

Corey

I’m always scared and alert, honestly. I walk around on campus, and I use my iPad to listen to music. I always have my iPad with me. I’m afraid the police are going to see me holding my iPad and assume it’s something else, and before I have time to explain what it is, I’m afraid I would be shot. I always have my headphones in, too. I replay this terrible scenario in my head over and over again. A cop is yelling at me to stop, but since my headphones are in, I can’t hear him and keep walking. He thinks I am running away and shoots me in my back.

3. Sense of helplessness

Adding to sadness and hyperalertness, many Black Americans also feel they have little control over interactions with police and cannot change the outcome. This is true regardless of their tone, behavior or actions. This is known as helplessness, a known symptom of trauma.

Lena

It’s a sad reality to accept that no matter how you dress, how you talk, a police officer will always judge you and think you’re a threat. I don’t think we have control over if we are going to get beat or not. Black folks could literally read a how-to-survive book and do every step, but cops would still find some reason to make the situation worse. We are always in a Catch-22. If we talk too much, we are talking back. If we talk too little, we are suspicious. I do everything in my power to avoid cops. Listen, someone broke in my house and I refused to call the police. I be damned. Because I think they would have assumed I was the robber and shot me.

Virginia

Every time I see a video, I feel an intense sadness. It feels like you are in the world’s worst … cycle I guess; some kind of sick joke. It’s like, damn, it happened again. Like nothing is ever going to change. Things may look like they are getting better, but then even when they are arrested, the sadness continues.![]()

Deion Scott Hawkins, Assistant Professor of Argumentation & Advocacy, Emerson College

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

==============================================================

Alecto, Megaera, and Tisiphone, you have taken on the task of afflicting the comfortable since probably a thousand years BCE, and added the faculty of comforting the affflicted somewhere around 500 years BCE. Help us learn how to do both effectively … and if we are too slow learners … don’t be shy about going at it yourselves.

The Furies and I will be back.