Experts in autocracies have pointed out that it is, unfortunately, easy to slip into normalizing the tyrant, hence it is important to hang on to outrage. These incidents which seem to call for the efforts of the Greek Furies (Erinyes) to come and deal with them will, I hope, help with that. As a reminder, though no one really knows how many there were supposed to be, the three names we have are Alecto, Megaera, and Tisiphone. These roughly translate as “unceasing,” “grudging,” and “vengeful destruction.”

Colleen’s and my fire seasons are ending or over, but Lona’s are just starting. However, this article, being, as it is, about preparation – and that specifically for an aspect of fires that most people, at least here, don’t think about – should be a good one to think about at any season.

================================================================

Firebrands: How to protect your home from wildfires’ windblown flaming debris

Josh Edelson/AFP via Getty Images

David Blunck, Oregon State University

As firefighters tried to protect homes near Lake Tahoe from one of California’s largest fires on record, they battled, windblown embers that kept sparking new small fires, some well away from the fire line.

Those embers, also known as firebrands, were a powerful and dangerous reminder that protecting homes is about more than avoiding a wall of flames.

Firebrands are pieces of flaming material that break off from burning vegetation or structures and are transported through the air. They particularly become a problem when heat and drought dry out grasses and trees and the wind picks up. Homes and other structures are at higher risk when they have dry fuel, such as leaves, needles or wood chips, on the structure or nearby.

That risk, and how it can easily be overlooked, crystallized for me in September 2020 when my parents were put on notice to prepare to evacuate as a fire neared their home in Oregon. I have studied wildfires for years, particularly how they spread through firebrands. Yet this threat made it real.

What protecting a home looks like

I was not concerned about a wall of flames reaching my parents’ home – they had a lush and green yard that was unlikely to ignite. Instead, what concerned me was whether my parents were prepared for ignition by firebrands.

Firebrands can travel over a mile by the wind and can be a major cause of spreading fires. In the Tahoe region, for example, firefighters couldn’t just focus on the main fire line in summer 2021 – they also had to patrol for spot fires.

At my parents’ home and several of their neighbors’, I used a leaf blower to clear potential ignition sources. I removed dried leaves in gutters and needles in valleys of roofs, and watered the dry mulch near houses.

I asked myself, if a lighted match or matches were dropped at a location, could they start a fire? If so, the potential fuel needed to be removed. In every home that I visited, I found locations where firebrands could potentially ignite flammable materials, despite the homeowners’ best preparations.

Tyler Hudson

What surprised me at the time was how little time people applied to preparing for firebrands, despite going to great lengths to protect their homes by watering the grounds. What I realized was that my parents and their neighbors, like many of us, envisioned protecting homes as stopping a wall of flames from reaching their homes. They did not appreciate that in some cases the greater threat could blow in by the wind.

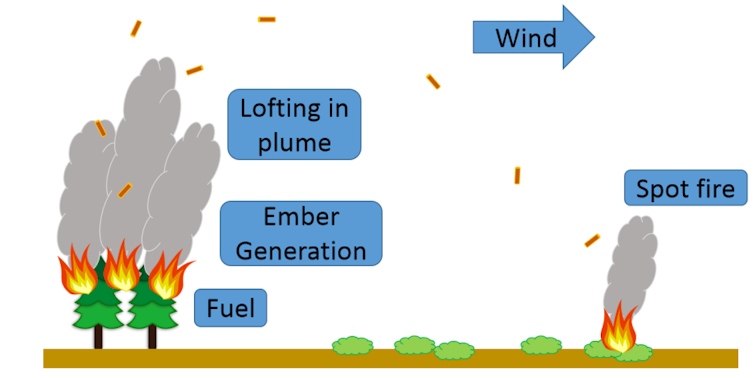

Three steps to firebrand-started fires

Fire scientists talk about spot fires as occurring in three steps: how firebrands are generated, how they are carried by the wind and how they land and ignite fuel. Fire scientists, including those from my research group, are actively studying each of these steps to be able to better predict and ultimately reduce the risks to communities from firebrands.

Firebrands are generated from burning vegetation or structures. Sizes of the firebrands can vary, but can be as small as several millimeters square.

Firebrands can come from burning pieces of bark, branches, cones or needles if the source is wildfires. For urban fires, firebrands can come from roofing, siding, particle boards or other flammable materials.

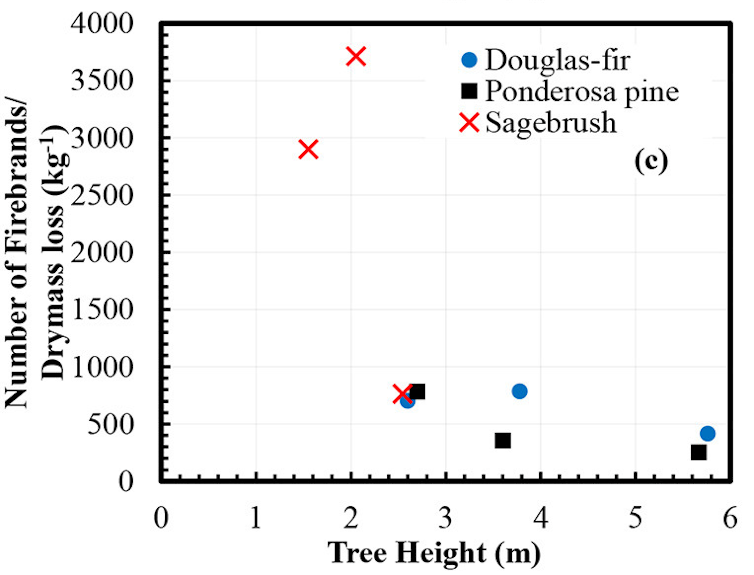

Over the past two decades, efforts studying generation of firebrands have often focused on quantifying the number of firebrands that land at particular locations as trees or other vegetation burns. More recently, researchers are working to estimate the total number of firebrands that are released when objects burn.

Adusumilli, Chaplen and Blunck, 2021, CC BY-ND

To estimate how many firebrands a fire generates, we set fire-resistant fabric squares around burning trees and shrubs, such as Douglas fir and sagebrush, and collected the firebrands that landed. By determining the total number of firebrands per unit of mass of the tree or shrub that burns, we can incorporate data into computer models to estimate the total number of firebrands released in a fire and where they spread. Ultimately, we hope these models can be used to better understand risks associated with wild or urban fires.

Many research efforts have focused on developing models that capture the physics of how firebrands are transported or where firebrands are most likely to land. The nature of the burning of firebrands as they are being transported is an important factor. Firebrands can be flaming or smoldering. Both can cause new fires.

The third step is ignition of fuels – like fencing, mulch and needles – after firebrands land. Researchers are investigating the heating potential or temperature of firebrands. Understanding this information is critical for implementing building codes and standards and best practices to better protect homes. We’re also working to better understand which characteristics of the fuels determine whether they ignite.

Adusumilli, Chaplen and Blunck, 2021, CC BY

How can homeowners reduce the risk?

So what can homeowners do to protect themselves from the risk of spot fires?

First, start with shifting your mindset about preparation to not if, but when a fire will occur nearby. I will admit that, as a homeowner who lives near a forest, I allow pine needles and leaves to accumulate on my roof. I make the excuse that I will have time to prepare in an actual fire. Yet, as I consider preparing for “when a fire” will be near me, rather than “if,” I feel more of a sense of urgency and responsibility.

Second, people in fire-prone areas need to educate themselves about potential ignition sources. Note that locations that are fire-prone are expanding. My parents’ home hadn’t been threatened by fires in the 30 years they had lived there – until 2020. One resource when figuring out how to audit a home’s risk is the National Fire Protection Association.

Certainly, at a minimum people to need to remove flammable material from on or near homes. In addition, they should consider ignition sources from structures such as decks and ensure that firebrands cannot be pulled into homes through ventilation ducts or other methods. Putting screens on windows and over ventilation ducts, using 1/8-inch holes, can be a simple, low-cost and highly effective way to stop firebrands from entering a house.

Third, consistently act to monitor and eliminate ignition sources, such as needles or leaves, that can gradually accumulate with time. Often it takes little effort to remove the debris, but it requires constant monitoring and prioritizing removal.

[Over 100,000 readers rely on The Conversation’s newsletter to understand the world. Sign up today.]

Certainly taking steps to educate, audit and then remove ignition sources from firebrands will not stop all fires from spreading to homes. But these steps will save many homes and help to reduce the risk to fire responders and communities.![]()

David Blunck, Associate Professor School of Mechanical, Industrial, and Manufacturing Engineering, Oregon State University

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

================================================================

AMT, this discussion is not so much aimed at firies as it is at those they protect – but that is a huge help. Anyone in any helping profession knows that half the battle is getting the client at least out of the way – and cooperating is even better. I’d say this is one to pass on to anyone in a fire-prone area, and to save – not exactly until fire season – but unti enough before it starts to begins setting up precautions.

Incidentally – if you always thought od a “firebrand as a person, yeah – this is where that metaphor comes from. “Loose cannon” is similar.

The Furies and I will be back.

8 Responses to “Everyday Erinyes #285”

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.

Thanks Joanne. For those of us in CA, we have 30 yrs. of our water districts telling us to put bark mulch down for water conservation during droughts that now add to risk of fire…sigh.

The Caldor Fire is holding at 76% containment with efforts to go after the more major newer spot fires this weekend ahead of our next red flag warning in advance of the weak system that might bring measurable rain further north.

My nephew and cousin’s families live in CA – but both are in Metro areas (San Francisco & LA). They’ve smelled the smoke, but they are not in a high-risk area.

My property actually abuts a 8,000 acre park, so I have a bit of concern. But it’s mostly deciduous trees – and no sagebrush. (I had no idea sagebrush gets to be ~ 9′ tall!)

We clearly need both infrastructure bills if we have any hope of making some headway against climate change!

Yes, the sagebrush height surprised me too. I think the only one actually at 9 feet is the one in the key which wouldn’t count – but 7 and a half to 8 feet is still taller than I’ve ever seen or heard tell of. Also considering that the other two species studied contain turpenes and sagebrush doesn’t, it appears insanely inflammable.

I waited after posting to sendmy email today, but obviously I didn’t wait long enough.

Nemless’s post

Freya’s post

Or, you can go to the bottom of this page (the central section, under the blank comment) and toggle right, once for Nameless, twice for Freya.

Thanks for this great article, Joanne.

There are a lot of differences between bush fires in the US and Australia, but in both, it is catastrophic to get caught in. Yes, be prepared and prevent bushfires as much as possible, and have a bushfire plan made before the season starts.

A bushfire plan consists of two parts:

1. All the things to prevent the fire from reaching you, clearing your yard, cutting the grass as short as possible, taking any bushes close to buildings away, clearing your gutters and filling them with water by placing tennis balls in the overflows, keeping the ground around the house wet and the roof too.

But also have all the things in the house you need when you get caught and can’t get away, like woollen blankets, lots of water, radio on battery and the like.

2: Your getaway plan: have the car ready with all your vital stuff like papers, computers, some clothing and food and water. Get your animals ready and load them up. And decide BEFOREHAND when you’re going to leave. Don’t wait to decide until you’re forced to leave. You’ll be too late. Leave at the moment you’ve decided on AND GET THE HELL OUT OF THERE.

I’m not going into all the details of a bushfire plan here; there’s a lot of information in your excellent article on that, Joanne. But making a plan beforehand, getting things ready and talking it through with your family members is essential. Most people lost their homes and/or lives because they panicked when a clear head working to a known plan could have saved their lives.

AND…here in Calif, we’re being warned to avoid breathing toxic fume-filled air. I don’t mind walking with a mask but my little dog won’t wear one!

Whoever can come up with an effective mask (in multiple sizes) that fits inside a muzzle will likely be able to profit from it.

I sent Mitch this as a series of jpgs. He says “hi!” to everyone, and commented,

I wouldn’t habve expect this to be much of a problem in FLorida – but then, the point of the article was that most people, even in widely known fire-prone areas wouldn’t think of this method of spreading.