Experts in autocracies have pointed out that it is, unfortunately, easy to slip into normalizing the tyrant, hence it is important to hang on to outrage. These incidents which seem to call for the efforts of the Greek Furies (Erinyes) to come and deal with them will, I hope, help with that. As a reminder, though no one really knows how many there were supposed to be, the three names we have are Alecto, Megaera, and Tisiphone. These roughly translate as “unceasing,” “grudging,” and “vengeful destruction.”

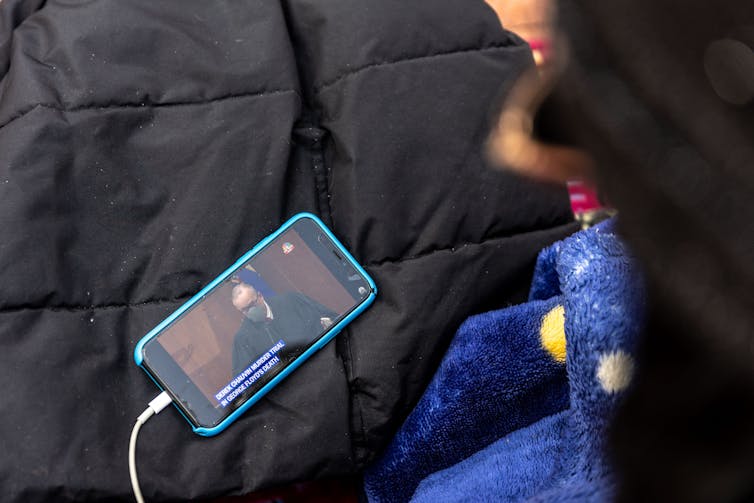

The trial of Derek Chauvin is scheduled to go to closing arguments Monday. While I doubt if anyone here watched every minute of the stream, we have probably sll been following it So I won’t comment much What I do have to say will be after the end of the article.

================================================================

Derek Chauvin trial: 3 questions America needs to ask about seeking racial justice in a court of law

Stephen Maturen/Getty Images

Lewis R. Gordon, University of Connecticut

There is a difference between enforcing the law and being the law. The world is now witnessing another in a long history of struggles for racial justice in which this distinction may be ignored.

Derek Chauvin, a 45-year-old white former Minneapolis police officer, is on trial for second-degree murder, third-degree murder, and second-degree manslaughter for the May 25, 2020, death of George Floyd, a 46-year-old African American man.

There are three questions I find important to consider as the trial unfolds. These questions address the legal, moral and political legitimacy of any verdict in the trial. I offer them from my perspective as an Afro-Jewish philosopher and political thinker who studies oppression, justice and freedom. They also speak to the divergence between how a trial is conducted, what rules govern it – and the larger issue of racial justice raised by George Floyd’s death after Derek Chauvin pressed his knee on Floyd’s neck for more than nine minutes. They are questions that need to be asked:

1. Can Chauvin be judged as guilty beyond a reasonable doubt?

The presumption of innocence in criminal trials is a feature of the U.S. criminal justice system. And a prosecutor must prove the defendant’s guilt beyond a reasonable doubt to a jury of the defendant’s peers.

The history of the United States reveals, however, that these two conditions apply primarily to white citizens. Black defendants tend to be treated as guilty until proved innocent.

Racism often leads to presumptions of reasonableness and good intentions when defendants and witnesses are white, and irrationality and ill intent when defendants, witnesses and even victims are black.

Kerem Yucel / AFP/via Getty Images

Additionally, race affects jury selection. The history of all-white juries for black defendants and rarely having black jurors for white ones is evidence of a presumption of white people’s validity of judgment versus that of Black Americans. Doubt can be afforded to a white defendant in circumstances where it would be denied a black one.

Thus, Chauvin, as white, could be granted that exculpating doubt despite the evidence shared before millions of viewers in a live-streamed trial.

2. What is the difference between force and violence?

The customary questioning of police officers who harm people focuses on their use of what’s called “excessive force.” This presumes the legal legitimacy of using force in the first place in the specific situation.

Violence, however, is the use of illegitimate force. As a result of racism, Black people are often portrayed as preemptively guilty and dangerous. It follows that the perceived threat of danger makes “force” the appropriate description when a police officer claims to be preventing violence.

This understanding makes it difficult to find police officers guilty of violence. To call the act “violence” is to acknowledge that it is improper and thus falls, in the case of physical acts of violence, under the purview of criminal law. Once their use of force is presumed legitimate, the question of degree makes it nearly impossible for jurors to find officers guilty.

Floyd, who was suspected of purchasing items from a store with a counterfeit $20 bill, was handcuffed and complained of not being able to breathe when Chauvin pulled him from the police vehicle and he fell face down on the ground.

Footage from the incident revealed that Chauvin pressed his knee on Floyd’s neck for nine minutes and 29 seconds. Floyd was motionless several minutes in, and he had no pulse when Alexander Kueng, one of the officers, checked. Chauvin didn’t remove his knee until paramedics arrived and asked him to get off of Floyd so they could examine the motionless patient.

If force under the circumstances is unwarranted, then its use would constitute violence in both legal and moral senses. Where force is legitimate (for example, to prevent violence) but things go wrong, the presumption is that a mistake, instead of intentional wrongdoing, occurred.

An important, related distinction is between justification and excuse. Violence, if the action is illegitimate, is not justified. Force, however, when justified, can become excessive. The question at that point is whether a reasonable person could understand the excess. That understanding makes the action morally excusable.

Court TV via AP, Pool

3. Is there ever excusable police violence?

Police are allowed to use force to prevent violence. But at what point does the force become violence? When its use is illegitimate. In U.S. law, the force is illegitimate when done “in the course of committing an offense.”

Sgt. David Pleoger, Chauvin’s former supervisor, stated in the trial: “When Mr. Floyd was no longer offering up any resistance to the officers, they could have ended their restraint.”

Minneapolis Police Chief Medaria Arradondo testified, “To continue to apply that level of force to a person proned-out, handcuffed behind their back, that in no way, shape or form is anything that is by policy.” He declared, “I vehemently disagree that that was an appropriate use of force.”

That an act was deemed by prosecutors to be violent, defined as an illegitimate use of force resulting in death, is a necessary conclusion for charges of murder and manslaughter. Both require ill intent or, in legal terms, a mens rea (“evil mind”). The absence of a reasonable excuse affects the legal interpretation of the act. That the act was not preventing violence but was, instead, one of committing it, made the action inexcusable.

The Chauvin case, like so many others, leads to the question: What is the difference between enforcing the law and imagining being the law? Enforcing the law means one is acting within the law. That makes the action legitimate. Being the law forces others, even law-abiding people, below the enforcer, subject to their actions.

If no one is equal to or above the enforcer, then the enforcer is raised above the law. Such people would be accountable only to themselves. Police officers and any state officials who believe they are the law, versus implementers or enforcers of the law, place themselves above the law. Legal justice requires pulling such officials back under the jurisdiction of law.

The purpose of a trial is, in principle, to subject the accused to the law instead of placing him, her, or them above it. Where the accused is placed above the law, there is an unjust system of justice.

This article has been updated to correct the charges Chauvin is facing.

[Deep knowledge, daily. Sign up for The Conversation’s newsletter.]![]()

Lewis R. Gordon, Professor of Philosophy, University of Connecticut

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

================================================================

Alecto, Megaera, and Tisiphone, to me one of the best moments in the trial was during the cross examination of the defense’s final expert witness, who cied an expert who “used to” believe in “positionary asphyxiation, but has retracted his statements.” The prosecution was ready for that. They had an affadavidt from the cited expert which included “many people have said that I retracted [my statements on positionary asphyxiation, but in fact I have never retracted and do not retract any of my statements on the matter.” How can you not love a trial attorney on either side who does his homework in anticipation of it beeing needed to ensure that truth gets told?

There is no guarantee exactly how a jury will vote, but I am feeling some hope … tempered by finding it difficult to trust a jury. We shall see. We shall all see.

The Furies and I will be back.

9 Responses to “Everyday Erinyes #262”

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.

Thanks Joanne–very clear to the lay person. Another element of effective prosecution was recalling the expert and using lab results question to eliminate the exhaust hypothesis when not allowed to debunk another way due to a ruling related to preparing for defense rationale. I suspect Chavin’s refusal to testify was at least partially due to his belief in the strength of the prosecution case.

“His belief in the strength of the prosecution case” – and or his (and or his attorney’s) reluctance to open him to cross examination by someone that competent. I don’t think even the Alt-Right playbook would work very well against this prosecutor.

From the article, it seems almost impossible to convict a white police officer for any degree of murder or manslaughter of a black man in the current justice system even when millions have watched it happen on video. Much will depend on the composition of the jury, that is the selection of the jury.

I haven’t followed the trial closely, so I don’t know what the final makeup of the jury is but I hope each individual member realizes this is a pivotal moment and they are making history. Not convicting Chauvin will have dire consequences, will be seized upon by Republicans/White Supremacists and will have the BLM movement take to streets like never before.

I hope the Furies can make the jury see sense.

I’ve been concerned aout the jury too. Glenn Kirschner has only mentioned it twice. Once during the selection of the jury he pointed out that jury selection is an art rather than a science. And once, I think it was one of the two senior police witnesses who emphatically testified that this was NOT a proper use of force, he mentioned that the jury (I don’t remember whether he said “all” but it was implied) picked up their notepads and started taking notes and he was very glad to see it. That’s not much to go on, but it is a little.

Very Well said, JD.

1. Yes.

2. Sometimes force is necessary to protect others. Violence never is.

3. No. Never!

It’s so clear, isn’t it, when one understands the difference between “force” and “violence.”

I worry that the jury will acquit Chauvin, leading to an explosion of rioting. Remember when those LAPD officers were acquitted of beating Rodney King? Of course, the Chauvin jury should not convict him solely to avoid violence; but they must serve justice and provide our society with closure.

Great one, Joanne

I would hate to even think of the jury acquitting this officer. Many watched as did others who video taped this confrontation of Chauvin forcing George Floyd out of his car, then slapping him down to the ground and kneeling on George Floyd’s neck for 9 minutes.

Listening to the trail the past two weeks, hearing various specialists, police officials/officers saying that what Chauvin did. was the only reason/cause of George Floyd’s death.

No one in their right mind, should even be considering/thinking of acquitting Chauvin.

Otherwise like everyone mentioned, we will see even more violence.

We need to put an end to this type of violence now. Finally showing these evil racist officers that their mistreatments of blacks must be stopped. That they will pay royally for their evil acts of violence.

Thanks Joanne.

reading this late, so glad he is convicted on all 3 counts